By J.D. Harlock

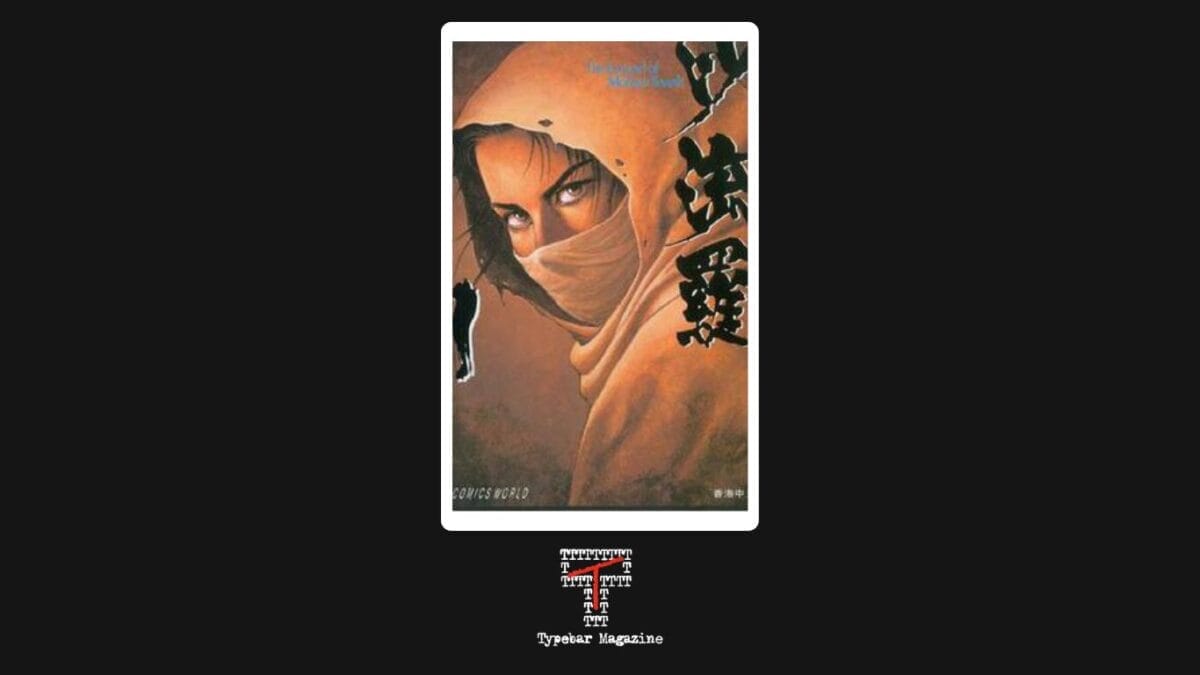

Published in Weekly Young Magazine from 1990 to 2004, The Legend of Mother Sarah is a post-apocalyptic manga following a mother’s search for her lost children in the wastelands of the Earth. Back in the radical 90s, it had the “Xtreme” elements required for international crossover appeal from the various demographics that constituted the worldwide fandom for Japanese comics. However, to this day, it hasn’t been fully translated into English, with physical copies out of print and scanlations needed to finish it.

This is because 1988 witnessed the release of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira, a milestone in animation, and thousands of motorcycle slides later, it’s still celebrated for introducing anime proper to the West. Despite these plaudits, the cinephiles who have elevated it to classic status tend to be unaware that it’s based on the critically acclaimed cyberpunk manga of the same name. Written and drawn by Katsuhiro Otomo, Akira was initially serialized in Weekly Young Magazine from December 1982 to June 1990, with the first American localization released in the US from 1988 to 1995. Otomo himself would direct and co-write the adaptation, heavily retooling the plot to fit the limitations in runtime. This approach necessitated cuts that resulted in the infamous mindscrew elements that came to be seen as hallmarks of the medium, for better or worse. Regardless, Akira proved once and for all that cartoons could be for adults through its intricate art, electronic soundtrack, and copious offerings of sex, swearing, and ludicrous gibs. The reputation that it attracted, however, would prove both a blessing and a curse to Otomo, forever branding him a revolutionary filmmaker in “oldtaku” circles who view Akira as both the summation and encapsulation of a storied career that continued long after it left theatres. Ironically, the source material is undoubtedly the full realization of the story and is by far the superior version. And yet, the film would be the yardstick against which Otomo’s subsequent efforts would be measured. Subsequently, the immutable perception that none of them have been as game-changing as Akira led to them being promptly discarded by potential readers and filmgoers, which is a shame, because the comic book series he followed it up with was The Legend of Mother Sarah. It was a collaboration between him and artist Takumi Nagayasu, and it was even more ambitious, possessing a vision that has proven far more prescient than his magnum opus.

As a consequence of large-scale warfare, the Earth has become uninhabitable, leading to an exodus into space. As circumstances would have it, a scientist would develop an environmentally clean bomb so massive that it could turn the Southern Hemisphere into fertile land while simultaneously burying the radioactive Northern Hemisphere in ice. Word of this technological breakthrough reaching the masses, endless wars erupt between the factions of Epoch and Mother Earth on whether or not to use it to repopulate the planet. The orbital colonies are inevitably dragged into this, compelling inhabitants to return to the surface and join the fray. Up till this point, Sarah lived peacefully with her family in one of the stations until one of the numerous terrorist attacks forced them to evacuate. In the debacle, she was separated from her husband, Bard, and three of her four children. The Legend of Mother Sarah picks up ten years later as Sarah roams this inhospitable world, searching for her remaining children. Still, she, too, is invariably caught up in the greater conflict.

From the premise, The Legend of Mother Sarah is just as bold in its prognosis of our modern woes as Akira, eschewing the action-centric cyberpunk societal collapse for a post-apocalyptic road trip amid attempts at establishing order. Compared to the reception that Otomo’s other works received, like Dōmu or Metropolis, The Legend of Mother Sarah is virtually unknown in the West, even though its serialization far outlasted any of the time he put into anything else. As mainstream superhero escapades of that era for adults clung to edgy antiheroes in no small part due to the massive influence of manga-inspired creators such as Frank Miller, Otomo offered readers a radical alternative with this follow-up by presenting us with a compassionate but strong maternal figure as the center of a science fiction epic. Even in Japan, the series stood out in the seinen scene (manga with a target audience of adult men) as it tackled subjects more often found in the distaff counterpart of the demographic, josei (manga with a target audience of adult women), like motherhood and marital discord. Unlike a lot of the unfortunate attempts by mangaka (Japanese comic book creators) operating in male-oriented target demographics, Otomo’s attempts to engage with these serious subjects never come off as underdeveloped, forced, or worse, misinformed, as it’s clear a lot of thought went into the writing.

What truly makes The Legend of Mother Sarah stand out from the glut of hyper-macho “after the end” gore-fests that were released in the wake of the iconic Mad Max: Road Warrior is its careful balance of light and dark, taking great pains to present the complexities in each dilemma Sarah confronts during her search. At a time when seinen manga like Berserk were still struggling to shift away from the juvenile black-and-white morality of unhinged fever dreams like Fist of the North Star, The Legend of Mother Sarah always tried to paint its scenarios in brushstrokes of grey when justified amid the brutal reality on display. Perhaps the most memorable moment in the entire franchise is when Sarah is presented with an impossible choice she has to make under extreme circumstances. On the run, as survivors from the fallen satellites are actively hunted down, Sarah is forced to smother her baby to death or else risk having the family hiding with them killed if the militias were to hear him cry. Gut-wrenching, it’s not a throwaway backstory to show readers how dystopian the setting is and why she is so desensitized to it, because she spends the rest of the story trying to find a way to come to terms with that one fateful decision. The characters who populate this setting are approached with the same care. Otomo ensures that each of his characters has hidden depths that you otherwise wouldn’t find based on their archetype. Take, for example, Tsue, the deuteragonist, a cowardly trader who initially seems to be a self-serving opportunist, even going so far as to trade arms. As he transports Sarah in exchange for payment, he is revealed to be driven more by desperation in this harsh environment as his begrudging respect for her mission leads him to become her staunchest ally, willing to go up against anything when coming to her aid.

Beyond the story and characterization, this equilibrium is upheld for its worldbuilding, where humanity is always found even in the bleakest of circumstances. This works because it’s evident that Otomo, recognized for his relentless research into the subjects he’s tackling, has done his homework and depicted the post-apocalypse with sobering realism. It humanizes the interpersonal dynamics, allowing us to empathize with the characters and their struggles even in a milieu that seemed so different from ours back then. The Peace Conference that forms the last major arc of the series is probably the most intriguing example, as it’s rare that such a pragmatic event would be such a prominent feature of the reconstruction process in this kind of plot, let alone play out logically. Either this kind of event is never considered or is glossed over entirely with a timeskip. Here, it fittingly acts as the culmination of the various arcs of The Legend of Mother Sarah, as Sarah’s presence among hardened politicians and soldiers reminds them of what’s at stake and how to behave, so that when the betrayals and sabotages occur, those among them who are truly striving for a better future abandon their ideologies to form a united front to rebuild the world.

Of course, this nuance serves the overarching narrative as Sarah encounters numerous obstacles that test her physically, mentally, psychologically, and ethically. At its crux, the core theme is that conflict resolution is a trying process that requires patience and dialogue, not kratocracy. Sarah is forced to resort to physicality to survive many times throughout the course of the story, and yet, it’s made clear time and again that her significant victories are a result of actions driven by compassion drawn from her experiences as a mother as opposed to senseless violence. What makes Sarah such a compelling hero is that she is not infallible. Even as her saintly nature is shown to lead us on the path to solutions following years of stalemate between the major political factions, she still fails to reunite with her children once she locates two of them, both having strayed so far away from a path she approves of. After many of her worst fears for them come to fruition, they remain adamant about figuring things out on their own and part ways with her, with the implication that their relationship with her might be mended at some point, but it will take time. Intentionally contrasting with the title, Sarah was never meant to be messianic, being just as flawed as the cast around her in an environment where even clear-cut villains are driven by some tragic backstory that warped their minds or some ruthless agenda driven by what they think will help the collective. At the end of the saga, she’s left to ponder what to do now that her journey is over. Ultimately, she accepts that the past she desperately tried to recreate is gone for good, finally choosing to find her place in the new world she helped create.