By Anna C. Webster

Have you ever looked at the map in a video game and thought: wow, I wish this was just the entire game? Or maybe you've found yourself playing a board game and thought: there's not enough pixels in this? You're in luck.

In the late 1980s, advancements in procedural generation tech gave rise to the booming "simulation" genre, which is characterized by games that model complex, real-world situations and environments. Players are often tasked with both responding to changes the sim throws their way while simultaneously trying to shape the sim to achieve their own specific goals: whether economic, civic, interpersonal, or in the art of war.

Although this subgenre of strategy games had been established prior to the modern moniker, the "4X" name (short for eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate) is believed to have originated from the 1993 release of sci-fi sim Master of Orion, wherein the four "Xes" were used to describe its gameplay mechanics. This snappy little device also perfectly described the typical gameplay verbs within other games in the subgenre... and it stuck. And if seeing a giant billboard for Sid Meier's Civilization VII while driving on the 405 S the other day isn't proof enough: this style of game has clearly stood the test of time. Yet for all the popularity of the modern Civ games, it’s one forgotten title from 1999 that would most accurately depict the arc of human civilization throughout the 21st century.

Sid Meier and the Rise of Civilization

Popular titles within the 4X subgenre include Star Trek: Fleet Command (2018), Stellaris (2016), and the classic Star Wars: Rebellion (1998). But undeniably, its singular most iconic franchise is that of Sid Meier's Civilization (often just called "Civ" for short). The now legendary designer and programmer Sid Meier had a knack for working on high-quality game releases to the extent that his name became included in titles as a pseudo-seal of quality: 90s publication Computer Gaming World declared it "a guarantee that they got it right."

And this was certainly the case with the Civilization franchise. Meier might not have been the lead designer, but with his name in the title and credits, it was bound to be a smash hit. Meier told Game Developer (née Gamasutra) that the original concept was "kind of like Risk brought to life with a computer," and was inspired by other recent simulation games like the equally-legendary Will Wright's SimCity (1989), which showed him that video games could be about "building things up" instead of the typical modes of violence and destruction.

The high-level gameplay of Civilization (which would quickly transform into a blockbuster series currently in its seventh mainline volume as of 2025) fits the 4X model perfectly: the player chooses to play as a prominent historical figure of a certain culture to build a political powerhouse all the way from prehistory to the 21st Century. The Civ games are "turn-based," meaning that during a player's turn, they must make strategic choices within their allotted actions: such as managing resources, engaging in diplomacy with other nearby civilizations, improving or building new settlements, or waging war.

The macro gameplay of the Civ games, however, is much more granular and technical. Players will need to do things like manage their government format of choice, GDP, taxes, army compositions, pollution... you know, all the glamorous things people really go into politics for. This combination of real-life civics and gameplay know-how would prove to be a massive success for the series with the launch of Sid Meier's Civilization in 1991, prompting the development and subsequent release of Sid Meier's Civilization II (1996) to much fanfare.

One of the standout features of the Civ franchise was their attention to historical detail, especially as the series (and its budget) progressed. While definitely not intended to be necessarily accurate, they did feature real historical technologies, "Wonders of the World," and cultural traditions of various groups from around the globe: everything from inventing the literal wheel to the cultivation of silk. The average layperson could expect to learn a few genuine historical developments and a greater understanding of general civics... all while the Aztecs overthrow Denmark or something. You know. Just like in history.

But there's one member of the Civ franchise that is eerily historically accurate - but for the future, not the past. And there's also a good chance you haven't heard of it. However, much like history itself, in order to understand this unorthodox installment we need to start at the beginning. And like any historical event you may have learned about in school, this fascinating title in the greater IP was almost entirely shaped by the circumstances that came directly before it. But far before the recent launch of Civ VII, before the rise of even the Civilization games of yore... there was copyright law.

War Breaks Out

It all comes down to names. An existing board game also called "Civilization" was published by British board game company Hartland Trefoil in 1980. This same game was published in the United States by Maryland-based wargaming company, Avalon Hill (now part of Hasbro). When MicroProse (Meier's then-company) wanted to use the same title for their admittedly very similar video game, they did what most Civ players would do: they sent out an envoy of diplomacy to broker a peace treaty between the two parties. And luckily, it worked out: both games, board and video, would be allowed to use the title.

However.

A little California company called Activision would purchase the rights to the "Civilization" name from Avalon Hill in 1997, prompting them to then sue MicroProse for infringing upon their copyright, citing that the original agreement between MicroProse and Avalon Hill was only for the production of a single game, and the recent release of Civilization II (1996) was therefore in violation. ...But they should have known better than to pick a fight with people who make strategy games.

MicroProse would in turn go on to purchase the board game's original company Hartland Trefoil in what can only be described as galaxy-brain retaliation. Only one month later in January of 1998, MicroProse would then counter-sue Activision and Avalon Hill, alleging unfair business practices (and a host of other things) on top of copyright infringement on the "Civilization" name... which they now held all the rights to as the owners of MicroProse and Hartland Trefoil. Activison, Avalon Hill, and MicroProse would opt to settle the messy suit outside of court. Avalon Hill was also made to pay $411,000 to MicroProse on top of letting them retain all rights to the "Civilization" brand. Well played, Sid.

However, there is one other peculiar outcome of this settlement: Activision, who had clearly been gunning to make their own Civilization game since their initial purchase of the naming rights from Avalon Hill, ended up securing an official "Civilization" licensure from MicroProse. They would then be legally allowed to release their own upcoming title... Civilization: Call to Power (1999). Notice the lack of "Sid Meier's" in the title.

A Brave New World, Indeed

The resulting installment was a fascinating spinoff (or perhaps a "sidequel") within the Civ franchise. Civilization: Call to Power (1999) was undeniably a Civ game based on its gameplay and its isometric, cobbled aesthetics, but when it isn't forgotten by Civ players entirely, it's best remembered for its many unique eccentricities. Despite being developed by an entirely different team with no involvement from Sid Meier or greater MicroProse whatsoever, the core elements of the 4X style remain firmly intact: players would begin on a small part of the map and must explore, expand, exploit, and exterminate, all complete with its now legendary "Wonder" videos which played upon each unlock. A few standout features include the spy/stealth units in warfare, the slavery system (and subsequent "abolition" development), a rather pointed distaste for lawyers (hmm), and the very cool potential of building underwater or space-based cities in the later stages.

However, it's this progression of the game's timeline that makes some real deviations from the Civ formula. "You soon get the feeling that the game is rushing you through the early eras of the world - the ancient, classical and medieval - so that it can show you the crazy shit it has in store later on. ‘Who cares about bloody horses and spearmen and rickety chariots clip-clopping along dirt roads and uncharted lands?’ it seems to say. ‘You’ve seen all that crap before, haven’t you?’" writes Robert Zak at Rock Paper Shotgun.

Most Civilization games mark the completion of a campaign when the player reaches somewhere in the early 21st Century. This would be the "near future" for games released in the late 1990s, but Call to Power made the unique choice of making the end date the year 3000 instead. And the far future? It kinda sucks.

Call to Power has five epochs or "ages" that the player can progress through: Ancient, Renaissance, Modern, Genetic, and Diamond. The additional two epochs in Call to Power (Genetic and Diamond respectively) are uniquely speculative and filled with biting commentary on both modern and future human potential. Sure, the player progresses throughout all of humanity's incredible achievements: discovering things like writing systems and industrialization, constructing the Wonders of the World, and even going to space. And then you get... an AI surveillance state (and an "AI Entity" with a chance of revolting against the civ which built it), an escalation of global warming from pollution that threatens the life of the planet itself, and even going to such extreme lengths to advertise products in a "Corporate Republic" society which immediately tanks citizen happiness levels. Hang on.

Is... Is it suddenly feeling a little bit too real in here?

Futurism remains a mainstay in Civ titles, but always with a distinctly altruistic flair: each new discovery and progression feels simultaneously like a miracle and the inevitable. That's just what we do as humans. We grow. We build. We progress. It's a downright celebration of all of the incredible advancements humanity has made, and always toward a better world. But Call to Power dares ask the question: what if the future kinda sucks in its own unique way?

Being willing to depict aspects of the future as advanced but also victim of its own unique enshittification was downright prophetic in 1999. The first of these future ages, The Genetic Age, is described thusly in the game's own words:

The advent of the Genetic Age marked the beginning of a period of powerful social and technological changes for the human race. It was an age of teeming, overcrowded cities on the verge of chaos, corporate governments, space exploration, and environmental fanaticism. It was during this time that arrogant scientists decoded the mysteries of life and set about to transform the human race. The wealthy lived decadent lives in fabulous penthouses, surrounded by genetically engineered clones and servants, while far below in the street the common people clashed with security forces or lost themselves for a few moments in the warm embrace of virtual reality. [Source]

And while we don't have nearly enough environmental fanaticism these days for my personal taste, this description feels very relevant to the present in 2025. While it was purely speculative to the folks at MicroProse, they accurately predicted the second Gilded Age, complete with the rising threat of an artificial-intelligence-fueled police state and the privatization of government. Unlike future dystopias that possess a more 1984-slant, MicroProse distinctly went for a more Brave New World envisioning of the era that would come next for mankind (which, I would argue, is also the more accurate comparison). And I mean, yeah, we do still go to space, but it's not nearly as cool or fun as we might have hoped because it's all corporatized!

Even the following Diamond Age feels like a stark departure from the depiction of humankind's expansion beyond earth in games elsewhere in the genre, not just Civ. In fact, 4X game Sid Meier's Alpha Centauri also released that year in 1999, and while it would detail some of the struggles humans would face in space (including but not limited to the waking of an eldritch hivemind creature - don't worry about it), it ostensibly retained the sense of optimism quintessential to the Civ games. To this day, most modern 4X titles are space-based or intergalactic-focused in some capacity. But even these similar forward-thinking titles lack the biting reality of "well, what if everything you built starts breaking because no one was hired to maintain the infrastructure" or "what if some rocketship-chaser lawyers come after you." These modern realities seem forgotten by other titles within the subgenre, and unexpectedly give Call to Power a sense of historical accuracy that none of the others possess. In fact, once familiar with Call to Power... the omission of these very obvious logical conclusions of current trends almost feels like a missed opportunity.

Call to Power received mixed reception at launch, with an aggregated review score of 73 according to now-defunct Metacritic predecessor GameRankings. It was even nominated for GameSpot's 1999 "Most Disappointing Game of the Year" award. Ouch. But a 73 and over 250,000 units sold was considered good enough for the folks at Activison, who would quickly greenlight a sequel: Call to Power 2 (2000) (note the lack of "Sid Meier's" and the "Civilization" title on this one, as official licensure would not be extended to Activision a second time). This one would fare similarly in terms of reception and sales numbers, and Activison would quietly sunset the Call to Power series and release the source code of Call to Power II in 2003 to the benefit of the stalwart Civ modding community.

But even after all of the lawsuits and nanobots, Civilization: Call to Power remains a fascinating entry in the series with an unusual cultural legacy. It's often completely forgotten or omitted as a cash grab "sidequel." However, in the eyes of those who grew up playing the title, it's best remembered for its remarkably prescient visions of humanity's far future: one characterized by wealth inequality, failing infrastructure, and chafing altruism. And perhaps that's only thematically correct for a title that was essentially born from a very messy series of lawsuits.

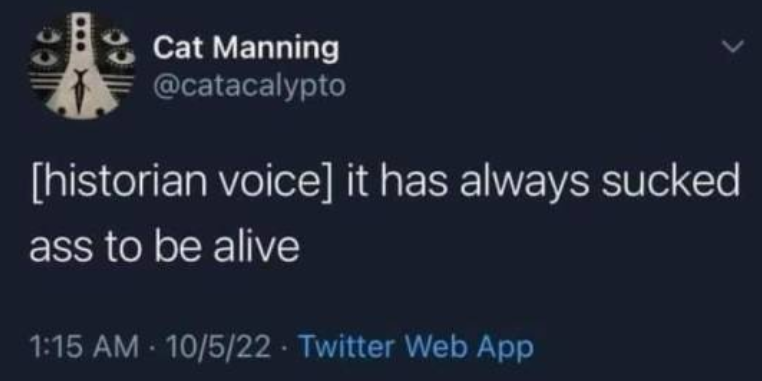

It's pretty clear to me that Call to Power's true, quiet legacy is that of a digital Cassandra more than just another 4X game: warning us of the dangerous potential of human progress. But for each one of their sarcastic little jabs, there's an even more important whisper like the flash of lightning after rolling thunder: "it doesn't have to be this way."