By Christopher Sloce

Fewer people than ever were happy about the NBA. I was high on the hog, watching the Detroit Pistons return from irrelevance after spending half my life in the gutter. Giddy as could be, I unmuted and refollowed everything related to the team (the 28 game losing streak in 2023-2024 was a genuine mental health hazard) and the league. What I found is, somehow, everybody else was in the opposite boat as me.

I noticed it first when Shaquille O’Neal couldn’t remember who coached the Pistons on national tv, and then on his podcast proudly said he didn’t watch them. Shaq is a color commentator, so I don’t look for him to be deeply analytical, but it was the pride in dismissing a team that was in the process of ending tripling their win-total from the prior year, winning 44 games instead of 14, something only the Pistons have done. Some people chalk this up to a dismissive attitude about Detroit, but the NFL flacks don’t talk about the Lions like this. Other contexts abounded. Stephen A. Smith got caught playing Solitaire during the NBA finals while a Cinderella Indiana Pacers team were on the way to upsetting the Knicks. Stephen A. Smith is a Knicks fan. It’d be preferable if he was calling in an airstrike. (As part of his contract negotiations with ESPN, he has stepped away from the NBA Countdown, after years of being one of its defining voices, to spend more time on other things, including a Sirius/XM politics show).

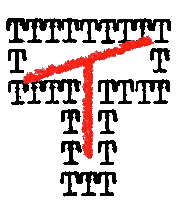

Speaking of airstrikes: for the 11th time in 13 seasons, a record was set for 3 pointers made. Maybe it’s because reigning champions the Boston Celtics were winning and had won the prior year by shooting an absurd number of 3 pointers (close to 4000 in 82 games) that it caused so much discussion, because people spoke as if the Boston Celtics braintrust had solved basketball. It was annoying. There’s a beauty in watching Steph Curry curl off of a screen and fire a prayer; this felt more like Marc Andreessen's group-chat talking about disrupting the water supply. The three pointer was wormwood, the great star falling from the sky and poisoning a third of the waters. That now these shots were being launched by power forwards and centers, who traditionally played close to the basket instead of 23 feet away, had taken on near eschatological proportions.

And from the sea came Victor Wembanyama unto the San Antonio Spurs. A 7’4 center with the mobility and shot diet of a guard was part of an evolutionary trend in the game: taller, more skilled players. That means a lot of threes. He was the most vaunted prospect since Lebron James, someone who would rewrite the entire era of the game. In the eyes of someone like Shaq, evolutionary centers with a perimeter game couldn’t hang with yesterday’s physicality. In his view, it’s a softer game now, and all they could do by getting backed down by Shaq is “shoot them motherfucking 3s.”

Wembanyama is also French. A majority of the top five players were, for the first time, European. People began to worry: there hadn’t been an American MVP in close to a decade. It got so bad people thought that Minnesota’s Anthony Edwards was a bastard son of Jordan. They also conveniently forget that Ant-Man wound up taking the trophy home for making the most threes that season (320).

With all these threes, all these Europeans, and all these experts citing all these reasons (by implication or otherwise), there was an NBA vibe shift akin to The Cut’s, and the NBA fandom was inundated with Questions About the Game. In 2024, after the start of the season, there was a sudden ratings drop of about 28%. No matter what else happened that season, the Ratings Question loomed over it. A variety of reasons were given, as were solutions. Commentators throughout the field pitched would-be solutions, including aforementioned gummy candy mascot, friend of the General, and podcaster Shaquille O’Neal.

Where there was once joy was suddenly anxiety, and everyone began trying to answer Mark Jackson’s now memetic question, a lament fostered because D’Angelo Russell caught a flagrant for knocking Jamal Murray to the floor: “What happened to the game I love?”Liking basketball had gone from beyond a hobby. Liking basketball meant you had staked out a position; you liked it in opposition to all of the concerns being raised.

I still do. I think basketball isn’t just a sport, though it is. It’s America’s “Beautiful Game”, a world export that is like our version of what we call soccer, and contains with it all the complications of world football and our country. Where the game is now makes sense when you look at the developments of the “commodified” aspects of the game: the development of its own logic towards dividing the labor of the game, its cultural impact, and that impact’s intersection with marketing. The existence of such does not invalidate the cultural value of basketball and it certainly doesn’t invalidate its beauty, which would constitute another essay. But the people who were supposed to explain the value of the game were interested in something else, and the questions of basketball felt like they were about something more fundamental.

A NECESSARY HISTORY OF THE NBA POSITIONAL REVOLUTION

The following story is a story of how a game went from “positions” to “responsibilities”, something that has been seismic in the history of the NBA. It’s a broad, imperfect history. As a method, I’ve mostly used MVP votes combined with championships won to talk about “defining players”. I use this rubric because this is the rubric everybody uses. There is certainly a place for Basketball in Sun and Shade or A People’s History of the National Basketball Association, but it helps to understand how the NBA braintrust views its history first and foremost.

We envision the league’s founding fathers as two colossi standing on the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts, Romulus and Remus with nothing above them but sky. Bill Russell was in Boston, Wilt Chamberlain was in Los Angeles. The unwritten rule of basketball history is to never let facts get in the way of feeling of largesse in the sport (you should read this essay in that spirit); it doesn’t matter that Chamberlain was only a Laker near the end of his career because his showmanship and finesse have tied him to the franchise forever. He feels like a Laker.

Throughout the sixties, the “Most Valuable Player” award went overwhelmingly to his somber, defensive counterpart, Bill Russell, who led Boston to 11 championships with an unbroken run from ‘59-’66. These were also two centers: tall players whose job is to guard the rim from easy points or other big men. From the 59-60 to the 78-79 seasons no wingman or guard other than prototypical “big point guard” Oscar Robertson won an MVP.

The fall line is the ‘79-’80 season: the year Julius Erving became the first MVP wing (shooting guard or small forward, basically players who hang out on the “wings” of the court) to win MVP in the modern era. Erving was known for athletic dunks, a hallmark trademarked in the flashier American Basketball Association. An equally important idea followed Erving: the three-point line.The three meant distances could become a weapon in the game. Its time would come: in the 1980 Finals, where Erving faced off against Kareem Abdul-Jabbar’s Lakers, he shot two three pointers the entire series.

A pattern was emerging: small-forward sized players like Magic Johnson (who was a point guard, but 6’8) and Larry Bird became the sport’s most important players, as opposed to the centers of the 60s and 70s. While Bird and Johnson’s teams both featured dominant centers like Robert Parish and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bird and Magic’s burst, speed, and playmaking meant (pun intended) the “center” of the game went t to what either of those players would do with the ball in their hands. It’s hard to argue against their dominance. 1980s championships went to either one of Magic’s Lakers or Bird’s Celtics, with the exception of the Detroit Piston’s bruising “Bad Boys” grabbing two in the late 80s. The MVP awards followed suit in the 80s: the only three players to win MVPs in the 1980s were Bird, Magic, and Michael Jordan. Jordan’s ability to turn any game to his side just by application of a will that seemed to encompass basketball meant that players on Jordan’s team were more there to do what he couldn’t do in that very moment. Jordan surrounded by specialists (and the greatest sidekick in NBA history, Scottie Pippen) could not only win but dominate.

Sometimes, in a sport, somebody embodies its great qualities so completely they become synonymous with the sport. Jordan is basketball the way Jimi Hendrix is guitar; even their gear (the Air Jordan, the Fender Stratocaster) are as much a stand-in for disciplines. He was a figure we could celebrate without complication, even emerging as a possible great at the 1984 Olympics. Here in the late 1980s/early 1990s is where basketball’s cultural dominance truly began. A little snapshot of our brains at the time: Michael Jordan did a commercial for McDonald’s with Bugs Bunny, basically our modernist American Loki, and that was so popular they made Space Jam. But even Jordan was human (watch him act in Space Jam for proof). He retired three times, two of which we remember fondly. The ghost of Jordan hung around the league, in forms that were uncannily close in some ways but neurotic, feuding with co-stars openly instead of privately (Kobe Bryant), in shooting guards who had a minor resemblance to Jordan’s style of play and were forced into a mold they never quite filled (Vince Carter), or Jordan himself in a disappointing run with the Washington Wizards. A search began for the next living legend. They found him in Akron.

Every great player exists in continuity with basketball as it was played before him. Kareem has evolutionary links to Russell and Chamberlain, Jordan combined Erving’s high flying style and Larry Bird’s tenacity. But they complicate our understanding of the game, highlighting lost parts and buried trends. This is part of what makes Lebron feel prophesied by the game up until that point. Two specific portents: Magic getting subbed in for Kareem-Abdult Jabbar, a big guard for a center, during the 1980 finals to play center and advice Bobby Knight, Jordan’s Olympics coach, gave to Trailblazers GM Stu Inman about what to do in the draft if they needed a center but could get Jordan (who gave up 5 or six inches to most centers): “Play Michael Jordan at center.”

Lebron James was the answer to a question implied by Bobby Knight’s quip to the Trailblazers brass: what if you could have Michael Jordan at center? Lebron has played every position, lining up mostly as a small forward and a power forward but passing like a guard and protecting the rim like a center when necessary. What’s more accurate to say is that if you have Lebron on your team, you have the four classic positions and a position called Lebron. He became the league’s most adaptable player, winning in multiple different contexts: as part of a super team (the Miami Heat “Heatles” with Chris Bosh and Dwyane Wade), a redemption arc run with the Cleveland Cavaliers, and in his dotage as a Laker. He was the best player on every one of those teams, even alongside fellow NBA legends.

He was also there to become the game’s goodwill ambassador and its dominant marketing figure. Lebron was more fun than Jordan, less likely to play one of the greatest games of his career hungover. He became a legend in his home state and came back to give them their only championship. Lebron married his high school sweetheart, and he danced on the side lines. His greatest controversy was an ill-advised free agency announcement and the maintenance of his hairline.

Everyone began a search for a Lebronian hybrid, not realizing he was as sui generis as Jordan. People began looking for someone who replicated Lebron as an archetype, not the lessons of positional advantage being unmoored. That would ultimately involve the NBA’s three point revolution.

Steph Curry was a leap in how the game was processed, because he took full advantage of that ABA export, the three ball, and became the greatest shooter in league history in the process. Despite only two MVP awards, he’s presided over one of the most dominant runs in history, including the winningest single season team of all time (the 2015-2016 Warriors, who bested the ’96 Bulls’ 72 wins by one game). What athletic advantages he had flew by bad scouts (I’ll remind everyone the Timberwolves drafted 4 guards that draft, none of whom were Steph Curry): his relentless motor allowing him to endlessly run off of screens and his quick release compared to thunderous leaping ability and a burst. He landed in a place that was committed to his advantages. Steph Curry could have just as easily been like his father Dell: a mere shooting specialist. But the dam broke. Steph Curry could shoot so efficiently from three it created an arms race mentality. In order to beat the Warriors, it would require making up the three gap.

Here we see a completion of the positional revolution. At a point in time, your strategy being built around a high usage point guard was mostly considered a gimmick. Point guards were there to pass and score if they absolutely had to. But with Curry, you could have him moving tirelessly around the court, able to pass to other great shooters like Klay Thompson and Kevin Durant. At the rim, you can put a low scoring but high IQ defensive forward like Draymond Green out to control the paint. More than anything, it gave the court two great centers of gravity: the three point line and close to the basket, all on a quest for efficiency. If someone can make three pointers at a high clip, they are encouraged, just as someone like Nikola Jokic (7’0 foot tall center and probably the best player alive, pound for pound) is encouraged to initiate the offense for the Denver Nuggets. Steph Curry’s dominance has been as much a victory of metabasketball. Now the game desires either broad generalists or specialists, all of whom are expected to shoot 3s if open.

It all calls to mind Antoine Walker, a lottery pick out of Kentucky. He was a power forward. About a third of his shots per game were threes. This drove everyone crazy. Someone finally thought to ask him: “Why do you shoot so many threes a game?” He responded, “Because there are no four pointers.”

To say this has had no effect on the game itself would be ludicrous. Players are expected to carry as many skills on them as they can; the archetypes that are fading out of the league are the most specialized ones. But the logic that led us to this point has always existed in the NBA game: scoring efficiently and setting up your teammates is good, a guy who can do three things is more valuable than a guy who can do two. The historical element of how we got to this point is rarely discussed. Even more rarely discussed is how the how the rarified air basketball finds itself in has had an effect on how the game feels, how the drive towards its marketable aspects has put basketball in conflict with some of the more democratic elements we could purport it to represent.

PERSONALITY, PRODUCT, AND PREP SCHOOLS

Sports entertainment is a commodity with an internal history you buy and sell as a part of the product. You buy Jordans to feel like Jordan. You also buy the sweatshop, the shoe store, and the intersection of those anxieties on what was supposed to be “just a game”.

For all of its utopian promise of escape for children scarred by ethno-religious war or the poverty embedded in the existence of the projects, the professional game is an industry that produces two products: one a product as watched, and one a product as experienced in a phenomenological sense.

In “Towards a Unified Theory of Uncool”, Ock Sportello writes:

The NBA’s crisis of cool concerns culture around it insofar as the NBA, more than anything else, is in the business of selling cool…[T]he NBA is itself a sort of advertisement for its aesthetics, personalities, and sneakers—if there’s an NBA deep state, the Nike headquarters is where they conspire. The league is, not coincidentally, the primary intermediary between many among its multiracial fanbase and Black American culture.

These players become oriented towards product: both the game and becoming one themselves. A starting point for the “crisis of cool” is a neoliberal economism that orients society towards an unending consumption and thus unending production.

If you feel like the league lacks genuine characters, one of the 2000’s NBAs greatest strengths, you are not wrong. The professionalization of the sport has favored an American middle class that can afford athletic trainers and gear, a class that can set them up with travel teams and send them to prep schools. That this coincides with the game’s obsession with positional efficiency, raw output of a player and what labor he saves, is not an accident. Large in part, true coolness is nothing if not inefficient. There is still a dialectic that takes place between common sense and the miracle of the game, but there are plenty of people who wouldn’t mind if athletes were AI generated spokespeople for Wheaties you could bet on.

This is, in many ways, incongruous to the spirit of the sport. Basketball can be played anywhere someone has thought to set up a hoop. It has been a game of farm boys and city park pick-up players and Jewish vacationers and high school kids on the rez. It’s in these folkways that something grew that captured imaginations from Milwaukee to Moscow, and it was these folkways that grew a game into a business doesn’t care that his game has had a democratic level of access, played by rich and poor, and with that, created professionals the people who benefit from all of the shared history with none of the initiative to give back.

Here’s a basketball folk tale. There was a mixed income housing development called 23 Oakwood that had a hard road to its development in Atherton, California, which was behind California’s state housing goals. The remedy was the city would build 16 townhomes, with up to 20% being labeled “affordable” or roughly priced to being about 30% of the area’s average income or three affordable houses compared to 13. Atherton’s powerful, including future Trump booster Marc Andreesen, raised hell at the prospect of this. One couple in particular asked for the development to be stopped outright, and if that request “should that not be sufficient for the state, we ask that the town commits to investing in considerably taller fencing and landscaping to block sight lines onto our family’s property.” Signing the letter was two time MVP Steph Curry.

“I LIVE HERE BUT IT’S NOT REALLY MY COUNTRY”: NBA AND THE MEMORY OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

The NBA is Black by majority. It is Black because of who made it the global phenomenon it is today, because of the cultural semiotics attached to the game. Many teams had white coaches and white owners, but you can’t remove Blackness from basketball. The NBA has been proud to be Black, and should be: basketball is one of the dominant expressions of Black identity in America. Black folkways are the game’s folkways, and the game exists where those folkways meet other streams.

Bill Russell and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar are not just greats in their sport; they were also a part of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1961, Bill Russell and six other players, refused to play in an exhibition game in Lexington, Kentucky when several black players were refused service at a coffee shop. One of the singular frustrations of discussing the Civil Rights Movement is how often history is discussed in a way that doesn’t connect it with other American struggles. Players not playing because the city refuses them hospitality is as much a strike over unfair and unequal working conditions as what happened in the textile mills of Lowell. Our misunderstanding of labor is but one part. The other part is our belief that because we idolize these players and we watch them, they owe us something. No small part of that has to do with who plays in the NBA.

For everything Bill Russell gave the Boston Celtics--and the organization are trailblazers in the NBA’s racial equality, though a good portion of the fanbase would rather make Brian Scalabrine jokes than celebrate that– the city gave him inattention, rarely selling out the Boston Garden during their 50s and 60s dominance. Boston gave him grief. His quote about the city in his autobiography Second Wind speaks volumes: “Boston itself was a flea market of racism… had all varieties, old and new…corrupt, city hall-crony racists, brick-throwing, send-’em-back-to-Africa racists, and in the university areas phony radical-chic racists…Other than that, I liked the city.’’ One night, the greatest player of the 1960s and a genuine hero had his house in Reading broken into. Racial slurs were written on the walls and he found feces in his bed.

The Harlem Riots of 1964 began when an off-duty police officer shot a Black teenager, and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, a Harlem native, knew it could have been him who died instead. This began a life-long interest in racial justice. When the NCAA banned dunking, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar knew the cultural valence of the decision, telling The Chicago Defender, “When you look at it … most of the people who dunk are Black athletes.” In 1968, Kareem refused to play for the USA team at the Olympics to protest of American racism.When Kareem went on The Today Show to discuss the basketball clinics he hosted in Harlem that summer, his decision came up. He told the host, former baseball player Joe Garagiola, that while he lived here in the United States, it wasn’t his country. Joe Garagiola said, “Maybe you should leave.”

As the sixties curdled into the 1970s malaise and 1980s Reaganite morning, the Black radicalism of the 60s was not so much fading out of its own poor decisions– though any political movement will make mistakes, especially under deep pressure– as it was vanquished by American state repression, chased into less disruptive terrain. It allowed for moderates to call the Black Liberation Army misguided gangsters and the Black Panthers a radical chic club; it chased the anti-capitalist elements of the Civil Rights movement into regroupment. This misunderstanding of the Civil Rights Movement as being vibes focused is a propaganda tactic in and of itself. In twenty years time, Fred Hampton’s Rainbow Coalition had become Jesse Jackson’s and even Jesse Jackson proved far too radical for Democrats.

There was some explosion of material growth in the 1980s for some, not for others. Reagan’s war on municipal and federal employment was an undeclared war on a Black middle class. The cities were inflamed with crack use; the AIDS epidemic was a background plague Reagan couldn’t be bothered with. However, he felt it necessary to disavow the H.R. 3966, the "Children's Television Act of 1988.'' This act would limit the amount of advertising to children to anywhere from 10 ½ to 12 minutes per hour.

Around this time Michael Jordan became the example of a celebrity-athlete and he knew he had to be careful with his words. This gained him millions, but there are unforetold costs. What would have happened if Michael Jordan, now an MVP and icon even before winning a ring, chose to endorse Harvey Gantt against arch conservative Jesse Helms? We can’t know, but we can know what he reportedly said: “Besides, Republicans buy sneakers, too.” It was true. Consumerism has always been a great leveling in our society with even children cut in on the bounty. Andy Warhol said the beautiful thing about Coca-Cola is you drink the same Coca-Cola as Elizabeth Taylor and we wore the same Jordans as Michael.

In 2008, somebody who exemplified similar cultural currents as the NBA ran for President. Here was a community organizer from Chicago, one with a decent jumpshot and enough charisma you can put him on ESPN without embarrassing himself. The NBA and Barack Obama were a match made in heaven.

It’s pointless to judge NBA players for identifying with Obama: they are highly paid Black professionals who understand how deep white scrutiny masks hatred in this country, and how that scrutiny is another form of surveillance. In a way, they were paying it forward after Jordan’s declaration about Republicans and sneakers. Perhaps he could have gotten through to Jordan; Obama made everyone feel like he understood, even me, unfortunately too young to realize Ron Paul was printing Lew Rockwell in his 1990s newsletter.

Then things began being spoken about in terms of necessity, a direct opposite to the message of Hope. Obama had to sell a number of ideas that fell into the same logics Clinton and Reagan without being crucified by some of those people it was harming. Presidents have always pointed to their experts to sell bad news, but Obama was able to imbue those expert’s analysis with what resembled a moral clarity and deep consideration of the unfortunate implications. We were told: we have to bail out the bankers who caused the financial crisis, they’re too big to fail, the experts say so. We have to join a NATO mission in Libya because America is the beacon of liberal democracy. The best healthcare we can have is a rebranded version of a Republican-helmed measure called HEART from 1993. We have to compromise because it's Doing Politics the Right Way.

It was here Barack Obama’s embrace of basketball helped. No other sport could have given that to Obama, because no other sport made him like other Black people like basketball did. There’s no reason to discount other sports and their Civil Rights History, but all one had to do was to listen to the people most terrified of Obama and their words about the league. NBA players were flashy thugs who relied on athleticism instead of fundamentals and Barack Hussein Obama was a Black radical Muslim socialist from Kenya. Obama’s embrace of the league allowed him to stake cultural ground more radical than he was as a political figure, and with that ground was the legacy of the Civil Rights movement easily caricaturized as a bunch of parades.

All of this culture cache made him an arbiter of a hip, urban centered liberal democratic order with the message everything was coming up according to plan. There was no reason to pay attention to the protests taking place on the hinterlands, other than to calmly explain to people that we were beyond waving Confederate flags and holding a sign that said “we came unarmed THIS time.” Be sensible. Why would you burn all this down? We’ve got a good thing going. You’ve got a President who fills out March Madness brackets, what more could you want? The questions persisted. The idea that we might ever escape the discussion of race started to look more cynical than anything. The answer came when, in four years, a man who spent much of the prior decade claiming Obama wasn’t from America became President.

“U BUM”: NBA IN THE TRUMP ERA

When Donald Trump was first elected, the only heartening thing about it was everyone you could ever respect thought it was the worst thing that had ever happened. Basketball was the official sport of the Obama era. Players were happy to go to the White House and see the man they voted for. Donald Trump was to be a negation of Barack Obama, a negation he has remained as a cultural figure. This explains why, to date, no NBA teams visited Trump’s White House.

The San Antonio Spurs' Gregg Popovich is the greatest NBA mind and coach to ever pick up a clipboard. He also became something of a Resistance sage for fairly eloquently describing his own dismay. Kyle Lowry, up in Toronto, said he thought the Muslim ban was “bullshit.” All Stan Van Gundy could say during a Pistons shootaround in Phoenix was, “most of these people voted for him. Like, shit, I don’t have any respect for that.” The Golden State Warriors refused to go to the White House, so Donald Trump rescinded their invite. Lebron responded by retweeting him with “U Bum!U bum @StephenCurry30 already said he ain't going! So therefore ain't no invite. Going to White House was a great honor until you showed up!”

As monstrous as he was, the first Trump administration settled, at some point after the midterms, into feeling like a number of misadventures than slow, fascistic creep. Not to discount any of the harmful policies pursued by the Trump administration, but after a point it mostly settled into incompetence and public distaste until the COVID-19 virus.

In summer 2020, the NBA invited the teams who had a snowball’s chance in hell at winning a ring to Disney World for the “Bubble” to qualify for the playoffs. When the season reconstituted itself, it was with protests against the police violence that killed George Floyd, Breona Taylor, and countless others as cultural ambiance. NBA teams wore Black Lives Matters shirts and knelt during the anthem, further linking the league’s image to its Civil Rights Lineage. Stephen Jackson, Former NBA cult hero and personal friend of George Floyd, spoke eloquently in Minneapolis:

"I'm here because they're not gonna demean the character of George Floyd, my twin…A lot of times, when police do things they know that's wrong, the first thing they try to do is cover it up, and bring up their background -- to make it seem like the bullshit that they did was worthy. When was murder ever worthy?”

Protests cropped up around the country, even in places no one would expect, and the American police continued murdering predominantly Black citizens. This created a feedback loop: with each overreach, the truth of the protests shone.

August 23, 2020. Jacob Blake was shot four times in the back by a Kenosha, Wisconsin police officer named Rusten Sheskey during a domestic disturbance stop. 40 miles north was Milwaukee, home of the Bucks, one of those remaining NBA Playoff teams. It was game 5 and they were preparing to play the Orlando Magic. They heard the news and made a decision. They didn’t come out. This would have been considered a forfeiture if not for one thing.

In solidarity, the Orlando Magic refused to play. In Minneapolis, Stephen Jackson’s ultimate prescription was protest: "So where do we go from here? We're going to the front line and anything you see, so be it, so be it, so be it. I want you to see it because this is real pain.” It was pain realer than basketball. The remaining NBA teams on that night’s schedule followed suit. Across American sports leagues, other teams stopped playing as well. The message was clear: we’re a part of this society, and in order for us to entertain you, we have to end the extrajudicial killing of all people by police.

Some players didn’t even want to continue the season. In a meeting with the NBA union boss Michele Roberts, the Lakers, led by Lebron James, and the Los Angeles Clippers voted to cancel the rest of the playoffs. Somehow the conversation kept coming back to money. At a peak in the discussion, the Lakers and Clippers walked out. The NBA season was almost ended by a strike.

Hours later, high profile players like Lebron James and Chris Paul had a phone call with someone important. It was somebody they had placed their trust in, someone they had helped elect. To let a spokesperson tell it:

As an avid basketball fan, President Obama speaks regularly with players and league officials. When asked, he was happy to provide advice on Wednesday night to a small group of NBA players seeking to leverage their immense platforms for good after their brave and inspiring strike in the wake of Jacob Blake’s shooting.

They discussed establishing a social justice committee to ensure that the players’ and league’s actions this week led to sustained, meaningful engagement on criminal justice and police reform.

The season was back on. The dominant image of the George Floyd protest went from burning infrastructure to Nancy Pelosi in kente cloth kneeling. The world was no longer upside down. All it took was one basketball fan.

NBA IN THE ICE AGE

Donald Trump lost his election that year but that strange period we called pandemic never ended. The knowledge that at any point America could be felled by a respiratory virus induced a new malaise, something New York based magazines call a “vibe shift” with a sort of erotic zeal. Donald Trump lost once, but the wreckage of the East Wing makes a definitive case that the Joe Biden Presidency never adequately dealt with him. Armed with the knowledge that at any point this could all fall apart, people began to change. In an imperfect world that was trying to recover, plenty of people decided they preferred the before, when Donald Trump was President, if just because it was a moment they could get a haircut and not have anyone stop them, if just because they didn’t see scary protests on the TV, if they didn’t have to pretend they got their shots on time, if they’d just shut up and play. As our overall culture shifts further right, all the artifacts of yesterday’s common sense come into question. That includes the NBA, arguably the most liberal coded of the major American male sports.

On the edges of the discourse, you can see prairie fires of reaction in a sport. You can safely joke that Karl Anthony Towns is on the downlow to a lot of NBA fans as long as you call him ‘zesty’. Nobody could beat the ‘96 Bulls because people are too busy doing TikToks. Jared McCain paints his nails, end of discussion. Even darker is a xenophobia that hides itself behind an interest in keeping the game as having its original, American character. America is a nation so focused on exports that one of our political thinkers developed a theory that any two nations with a McDonalds won’t go to war with each other. That is a logic endemic to capitalism: the total pointedness of society to continuing overproduction, one it ends all political strife. It never does; what it breeds is new answers. In the age of ICE, it’s no accident we decided something is wrong with basketball because some of the best players are European.

Sport media’s attitude towards basketball coincides with what we can call an open rightward turn. Barstool Sports is run by anti-union Dave Portnoy, so terrified Zohran Mamdani is going to nationalize calling 19 year old women a smokeshow he might run to Newark. When Stephen A. Smith isn’t ignoring a thriller Eastern Conference Finals, he’s lambasting Jasmine Crockett for not being deferential enough to Donald Trump. Pat McAfee is a shockjock and would-be Aryan superman; when he isn’t spreading vicious rumors about college student’s sex lives and forcing those same students to go into hiding, he has Donald Trump on, who said “I’m only joining you because I hear you say such nice things about me from your very large audience.”

With that, football takes up more of the landscape: a sport where owners colluded to keep Colin Kaepernick out of a job. For the American reactionary imagination, football is akin to the Aztec “flower wars”, ritual battles that prep the brain for blood. It is to the institution of American masculinity what the English boarding school was for the English elite: where you learn to kill. Donald Trump tried to buy a football team, not a basketball team. And there’s a very simple reason the NBA doesn’t have as much purchase amongst these types: the NBA lives here but it’s not the NBA’s country, to quote Kareem.

You don’t have to look far to see how acceptable talking about basketball unlike any other sport is. At the beginning of the essay, I linked a piece far below my own standard about NBA ratings (here it is again). The back half of this piece discusses topics all found in the article by Ethan Strauss, a Golden State Warriors beat writer (besides a single mention of Bill Simmons saying the season has too many games, making this a rare time I agree with Bill). Reasons cited by Strauss include the NBA’s social justice focus turning the sport into a “woke pinata” alongside a lack of continuity (it’s pretty easy to fall behind in an NBA season) and, gasp, too many top European talents in the sport. In fairness to Strauss’s original piece: it’s obvious he’s not denigrating basketball for these things so much as he’s trying to diagnose the problem. This is also a well worn beat for him, one he was walking back in 202o as well. The issue with his diagnoses are as follows: 1) ratings are important for TV owners, not fans and if you think that’s a cop out, 2) it means you have to cede some of basketball’s strengths. And that means ceding parts of the argument to someone like Charlie Kirk. You don’t have to think long about why he might have had a problem with basketball. But it’s telling when his breaking point with the league is: 2011 and 2012, when Lebron James finally began winning rings. Charlie Kirk was a pretty good youth basketball player; he, too, in his own way was asking what happened to the game he loved.

Q: WHAT HAPPENED TO THE GAME I LOVE A:

That grand memetic question, “What happened to the game I love?” has been a stand in for anything you don’t like or feels abrogated to the spirit of the game for you. Fitting, then, that Mark Jackson was also as much of a jackass as any of the anti-NBA right we’ve talked about here: people wonder why he doesn’t get another shot coaching and it’s probably the fact he forced team prayers on the Golden State Warriors while getting caught up with sex workers. All he said of Jason Collins coming out of the closet was “Not in my locker room”. Hypocrisy abounds. What else is new?

At base, conservatism believes that there are worthy subjects of societal protection because everyone who doesn’t get what they need either didn’t deserve it or weren’t meant to, and any change of this is like resetting the laws of God. William Buckley and Mark Jackson both sit astride history yelling not just “Stop!” but also “Go back!”

In some ways, he doesn’t deserve an answer. But here are two for Mark Jackson and his ideological coterie. The first is for the people who are afraid of sports that change along with the world, and think that players are there to shut up and be bet on. For them, my answer is, “Nothing happened, you just never loved basketball.”

Here is the second answer: At the end of the Hillbilly Highway is a city that became the home of my ancestors, one of America’s poorest and Blackest. It was also a proud city, one that housed one of America’s strongest industries. It was a team they named after a machine part that converted temperature and pressure into motion. It was a destiny decided by the name, like so many names before. The team became synonymous with the same grit the city was associated with, embodying its imagine in a way teams rarely do. They managed to win two rings they never had any business winning against Larry Bird and Magic Johnson, never playing the way anyone wanted them to, even striking up controversy when they said if Larry Bird was Black, he’d be some other guy (a statement that’s as true about race as it’s untrue about basketball prowess). When Nelson Mandela was finally freed, he wore that team’s gear and spoke with UAW members who campaigned to get him freed. It defined something about that city hearkening up north, some industrial north star. I could understand that place because where I was born, everything was rust, too, and the team defined what I thought we should be as a people.

And for years, they lost in every way they could. Mundane, unimaginable, ugly. They played the way the world was starting to feel. But when I felt like things were gone forever in this world, they started to win again. But there was a problem. They were owned by a man who got all of his money from an equity firm called Platinum Equity that owns Securus Technologies, who take $12.99 from prisoners and their families just so they can speak on video for 20 minutes. A sport defined by Black ingenuity is part of the investment portfolio that also feeds off of Black pain. When they win, sometimes I think about all this, it’s too much, and I tear up at the enormity of it all and how one court can hold it all. Only in fragmentary moments in our culture does America happen like it’s supposed to. Basketball just makes it happen in 24 seconds, until the shot clock rings.

Christopher Sloce is from Wise, Virginia and lives in Richmond, Virginia. He publishes nonfiction regularly and short fiction intermittently. His ezine Kentucky Meat Shower is hosted at kittysneezes.com along with his monthly culture column Apophany. His contributions to the studies of Football Metaphysics are conducted alongside Raven Mack and others here.