By Alexander Taurozzi

[Editor’s note: In the days after this essay was finalized, the United States kidnapped Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. A new wave of threats against Greenland, Denmark, and Iran came shortly afterwards (this isn’t to mention the federal government’s militarized and lethal occupation of Minnesota). The shifts to the global diplomatic paradigm are too swift and numerous to update the essay daily. However, the core of the essay–a writer asking about whether the United States can ever truly be trusted–remains as relevant today as it was when Richard Rohmer penned Ultimatum in 1973].

Richard Rohmer’s Ultimatum – the story of the United States invading Canada for its energy – seemed ludicrously implausible not even five years ago. However, when it was published in the early 1970s, the United States-Canadian relationship was frosty, only to warm during the subsequent decades, wherein hypothetical invasions of Canada were played off as cartoonish buffoonery such as in 1999’s South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut.

With every passing day of the Trump era’s chaotic tariff system and aggressive “annexation of Canada” language – which at the time of writing has mostly cooled in favour of the United States administration declaring war on its own cities and, at the time of writing, eyeing a possible invasion of Venezuela – Ultimatum is a historical literary oddity with striking parallels to the contemporary state of North American relationships.

Rohmer envisioned a way out for Canada if such a situation were to emerge between the capitalist bed-mates, and in the year 2025, a solution is needed more than ever.

Ultimatum envisions a Canada and United States with a reasonably historically accurate past. As in, besides the events in the novel, everything in the past is based on geopolitical reality. The present events of the novel told by Rohmer (because the characters are very much Rohmer) is seen through the perspective of a WWII veteran, a fighter pilot, and proponent of Canadian Arctic sovereignty. The future Rohmer envisions for Canada is harsh to say the least, but well, we’ll get to that in a moment. The decisions people make within this temporal frame are ultimately the decisions Rohmer would make for a brighter Canadian future.

As a political manifesto, Ultimatum seeks an equal friendship between the two North American nations, built on all the capitalist buzzwords such as free trade and national sovereignty. In the novel, Canadian politicians (including the Prime Minister, leaders of the opposition, Canadian media) are firm on Canadian unity and pushing back against any United States interference. For the most part, even the President is hesitant to take over the entirety of Canada. Which most Presidents perhaps should be wary of, seeing as the price to take over Canada, not to mention the thousands of kilometers of untamed wilderness, is astronomically high.

Within the novel, there is a real warmth to the relationship between the two powers, one that Rohmer saw in the battlefields of WWII’s European theater. The President calls the Prime Minister up on his personal telly to shoot the shit the only way political heads of state know how: talking about reelection. Except, the President quickly shifts gears to a worsening energy crisis hitting the United States hard this winter, and Uncle Sam needs enough natural gas to keep the children warm on Christmas. Lucky for him, Canada is as militarily equipped as a stocking stuffer and has enough natural gas for all the good girls and boys.

Published in 1973, the events of Ultimatum take place in the imagined 1980s. In the reality of 1973’s energy market, the United States faced an embargo on gas and oil from the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries, as did any other countries who supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War. To circumvent these issues, the United States and Canada start planning exploration and ideating potential Arctic pipelines. After a long process that took up most of the 1970s, the Mackenzie Pipeline was constructed, and by 1998, over 3.3 billion cubic feet of natural gas was transported from Canada to the US over 800 km+ of pipeline every single day. Current estimates on the Arctic’s natural gas are about 90 billion barrels of “undiscovered conventional oil resources”, and about 30% of the world's undiscovered natural gas resources.

It is important to note, the same year Ultimatum was released, Rohmer developed a non-fiction book dealing with the ramifications of development in the Arctic. Titled, The Arctic Imperative. Rohmer takes the stance of a “careful developer”, assuming that the Arctic fuels will be exploited and developed. The book did not sell well, yet, a majority of the ideas found within the book are explored in Ultimatum.

Rohmer emerged as a fighter pilot during the second world war. He was an accomplished airman taking part in 135 missions across the European theater, an expert at maneuvering planes. He was vital for the Battle of Normandy in reconnaissance and sending intelligence, knowledgeable of military tactics and deceptions. Rohmer watched Canada and United States troops fight side-by-side on D-Day, helped restore the Netherlands to Allied control, and went on to teach future pilots his methods. Rohmer lived in Canada as a lawyer, and later an author. He had an active civic imagination, and throughout Ultimatum, he is concerned with the ideal governance of Canada. It is what Rohmer would have done, and truly is an insight into his mind.

In Ultimatum, Canada builds a pipeline to the North, but suffers numerous setbacks from an overly bureaucratic government, and the biggest setback, a resistance movement led by various First Nations groups in the North. To be specific, the pipeline keeps getting blown up with timed explosives by guerilla forces. The United States, dealing with the aforementioned energy crisis, presents its northern neighbor with a three-part ultimatum: (p.17):

- Part 1 - “The aboriginal rights of the native people of the Yukon and the Northwest Territories will be recognized, and that a settlement will be worked out with them at once along the lines of the Alaskan model.” (ANCSA)

- Part 2 - “Canada will grant the United States full access to all the natural gas in the Arctic Islands without reference to Canada’s future needs” (based on the National Energy Program that restricted foreign competition and secured Canadian interests in the energy sector)

- Part 3 - “And finally, I want a commitment that the United States will be allowed to create the transportation system necessary to move the gas as quickly as possible from the Arctic Islands to the United States. This commitment will have to conclude free access to the Islands across any Canadian territory, which may provide a practical route.”

Oh, and all of this has to be delivered by 6 pm the next day, eh. Great.

The thirty-something hours of this books events feels like an eternity, as for one hundred and twenty-five pages, the Prime Minister of Canada’s only actions are, ahem: rally the Cabinet for a 9am meeting, create a measured statement to the media, have a whisky with the Governor General (head of state representing the King, but only in a ceremonial way), debating with the opposition as to the best course of action, meeting old political allies, make a speech in Parliament, and explain to the editor of the Toronto Star and CBC, “for the love of God, do not panic the people”.

“I don’t want newspapers to have four-inch headlines saying, ‘Crisis Canada’ or ‘U.S. Ultimatum.’ I don’t want the television and radio programs to be interrupted with emergency bulletins. I would like to see a sort of normal, everyday reporting of the U.S. proposals and how we are dealing with them. My concern is that the people of Canada should not be panicked.” (p.41)

It is as boring to read as it is to explain. Increasingly, it appears the Prime Minister is a stand-in character for the author, a narrative tool that voices the opinions of a certain WWII veteran. For the majority of the reading, the Prime Minister is very dissimilar to his real life counterpart, Pierre Elliot Trudeau (1968-79, 80-84), the father of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau (2016-24), the famed political leader who signed the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Pierre was charismatic, he had a sharp intellect, he was witty - “Trudeaumania” existed for a reason. Pierre was confident. The Prime Minister in Rohmer’s book is not confident. He is pragmatic, demanding of his staff, and demonstrates none of the intellect or charisma of his counterpart. In short, he appears to be more like Rohmer.

The President of the United States becomes a secondary character as well, visiting the various sites around Canada for energy and natural gas, testing pipeline projects and meeting various officials. The most gripping event is the pipe pressurizes to burst, and a valiant Harold saves the President from falling on his ass, which is the most amount of action we get in this book. Essentially, the President is the other side of the shower argument Rohmer is having with himself about the Arctic Imperative.

The President effectively scopes the place out, trying to see what gas pipeline infrastructure is in place in time for his annexation efforts. Kind of like a boring version of Airforce One, where instead of Harrison Ford killing terrorists, it’s the President talking to pipeline engineer Harold Magnusson from Churchill, Manitoba. Rohmer was a pilot, and the President is a pilot, and hell, the President is such a good pilot he kicks the main pilot out of the controls and flies the vessel down himself. The President is the type of leader a military man Rohmer idealizes; a man of action, certain, knowledgeable.

“Air Force One, with the President at the controls, had slowed down to 250 knots. To the citizens of Churchill, Manitoba, 2,000 feet below, the Boeing 747 appeared to be hovering there like some great goose followed at a respectful distance by a brace of ducks…The President banked the big bird in a shallow turn to the left…The President send to the captain, “Ever been here before, Mike?” “No sir, I haven’t.” “Well, let me tell you a little about this place.” (p.85-6).

Very astute of you, Mr. President, and a tad romantic (at least, I hope).

I hesitate to tease Harold Magnusson, as he might be based on a real person. The real Harold Cecil Magnusson (23rd Fd Coy) was a military engineer in the Canadian army. He was killed in action on September 26, 1944, during Operation Berlin, a Canadian operation to recover airborne troops trapped by enemy forces across the Lower Rhine, Netherlands. The men trapped were Operation Market Garden. In May 2025, Rohmer attended the memorial in the Netherlands commemorating Canadian troops lost in Operation Market Garden, revealing at least a tangential connection.

The President and Magnusson have a very interesting discussion where the President fact-checks Magnusson. In addition, they have a ten-page discussion on Melville Island about underwater Arctic pipes, how they work, and exactly what the specifications of the project are (with graphs!). Here is an example of the workings of Arctic Imperative in the novel - this is Rohmer’s idealized future of Canadian oil infrastructure in the Arctic.

The wrinkle in this shower argument comes in the form of the Indigenous peoples of the Arctic. Sam and Bessie are a couple of Inuk origin living in the Arctic. The pair are part of a network directly responsible for bombing the various pipeline development projects, and our only Indigenous Canadian viewpoint. For much of the book, this is what we know about them. However, Sam becomes the deus ex machina contact of the Prime Minister, approached to broker a deal between the First Nations peoples of the Northwest Territory / Yukon and the Canadian government - we can’t do this without you! In the middle of the Yukon, they come to a settlement similar to ANCSA at Parliament, satisfying the first part of the ultimatum. The Prime Minister has all the parts he needs to come to the table. Except, oh wait-

By the time 6 pm rolls around, Canada denies the President and his terms. The President is furious, and the United States declares war on Canada.

Wait, so why was Sam agreeing to the terms of the ultimatum necessary if war was going to break out anyway?

If Richard Rohmer’s mind and thoughts are found in Ultimatum, in a very literal sense, not filtered through a novel fiction lens of any sort, then Sam’s involvement raises questions. In fact, he seems to be viewed as a revolutionary figure. And eventually, friends with the establishment. As the only First Nations person in the novel of consequence, it is Rohmer’s view that Indigenous folks are either a) righteous, noble revolutionaries removed from society, or b) friends of and eventually good Canadians willing to bury the hatchet and forget about hundreds of years of injustice.

In Ultimatum, Sam is written as the scapegoat for a plot revolving around North American colonial-capitalist unity and politics. The Indigenous person as the scapegoat is a familiar stereotype. During the negotiations ending the War of 1812, the Treaty of Ghent, the British abandoned the terms of their First Nations allies in negotiations with the US. In 1830, Andrew Jackson passed the Indian Removal Act to forcibly relocate Nations from the southeast to west of the Mississippi River. In 2024, the minority Liberal Finance Department attributed the budget deficit to settling Indigenous legal claims (deficit: $61.9 billion, legal claims: $16.4 billion). Scapegoating Indigenous peoples is a practice still happening in Canada, 2025.

The UN has decreed First Nations peoples have suffered from historic injustices as a result of the colonization and dispossession of their lands. Members of First Nations have felt loss, humiliation, frustration, and anger as oppressed peoples. In 2025, there are currently 49 reserves across Canada facing boil water advisories, excluding BC. Canada has demonstrated a complete lack of care for Indigenous individuals' health and safety, and human rights violations in regards to the rights of self-determination and inclusive governance with First Nations leaders. During the discussion of Canadian responses to Trump’s threats, First Nations folks were barred from the table through omission.

To bring this back to the Ultimatum: Sam is in the trope of the “Noble Savage”. He is a idealized saviour to the colonial state of Canada and uncorrupted by North American politics. A contradictory man who fights the Canadian government with bombs and submits to their will. He is innately good and morally superior, even willing to settle with the Prime Minister and forgo his goals for the goals of the Canadian state. Rohmer is a product of the Canadian colonial project, and no matter his intentions, he depicted Indigenous folks in a derogatory way. He treated their aims and goals, the complex process of arbitrating and negotiation with Indigenous leaders in the Arctic, as a simple conversation and checkbox between two men. The process of decision making between all stakeholders is completely ignored in this depiction.

This is where Rohmer reveals his hand. Ultimatum is not a realistic portrayal of the crisis. In real life, there was never a First Nations bombing of pipelines. There was never a Indigenous person who could speak for all Nations in the Arctic. And the United States would not give the Canadian government an ultimatum - they would simply try to destabilize the country anyway.

Panic sells. Ultimatum caught the nation's eye as the book became Canada's best-selling novel in 1973 because it was gripping larger panic. This particular brand of anxiety is truly an emotionally untapped market for new ideas. Political science professor Stephen Azzi dove into the 1970s collective anxiety towards US invasions. During this period of US history, the civil rights protest, the police brutality, the war in Vietnam, Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy assassinated, riots in over 100 US cities in 1968 (the same year that MLK and Robert Kennedy were assassinated); to Canadians, Uncle Sam’s Americans appear to be an ‘inherently violent’ nation. Ultimatum is part of a tradition in the 1960s of Canadian authors tapping into this collective anxiety. Other books of the same period are The Trudeau Papers (Adams), Exxoneration (Rohmer’s sequel), and Killing Ground: The Canadian Civil War (Powe). The plots of these books echo the issues of the Cold War on both sides; energy crises and Quebec separatism (a larger issue).

In the lead up to Ultimatum being published, Canadian anxiety was at a high. At this time was the US oil tanker Manhattan attempting to navigate the Northwest Passage in 1969-70, which the US claimed was international waters. The Canadian government extended their territorial claims to the north, based on the ‘right of self-defence’. In 1970, Henry Kissinger, in his role as assistant to the president for national security affairs, sent over a recommendation to apply pressure to Canadian oil and wheat exports, destabilizing the Canadian economy. In 1971, Nixon imposed a 10% surcharge on Canadian imports, and in 1972 announced the end of the special relationship that Canada and the US had. It all comes back to trade.

Rohmer fought side by side with the forces of the United States during World War II. In a sense, the US betrayed their northern neighbors over the course of the 70s, and Rohmer, like many Canadians, was feeling that sting. Ultimatum is the complexity found in Rohmer's depiction of the events of the 1970s; how literal pipelines work, the interests of the United States in strategic resources, Canadian anxieties, and how he felt we should all come together.

How does the context of Ultimatum align in contemporary times? The current United States administration still desires energy in the midst of their tariff war, so much so that the tariff on energy is far lower, resting at 10% (a rather unsurprisingly stable number, despite the back and forth with Ontario premier Doug Ford threatening to withhold energy, the tariff increase of 35%, and Trump's tariffs raising US energy costs and blaming previous administrations). Is the United States in an energy crisis? President Trump seems to believe so, declaring a “national energy emergency” shortly after taking office in January. Is the U.S using an energy crisis as a pretext to declare a national emergency, and part of the response is bullying Canada? Shit seems to rhyme, doesn’t it?

In late 2025, we are experiencing a climate-fueled energy crisis. Governments around the world have more options for renewable energies and technologies available. Control of the Arctic is now divided between Russia, the United States, and China. Since 1964, 90 major offshore oil and natural gas discoveries have been made in the Arctic, and estimates put the amount of oil at 90 billion barrels of oil. Arctic plans are coming from everywhere, and one place where Rohmer is correct is the lack of a strong Canadian response and/or policy to the Arctic. Specifically, a united one.

The relationship between the US and Canada grew only closer post Ultimatum’s release. NAFTA and other free trade agreements took form in the 1980s between the governments. Did you know it was common for Canadian PM's and United State Presidents to play golf together? Reagan and Mulroney, Harper and Bush, Clinton and Chretien. A brotherhood founded on a shared love of sport. The relationship between Canada and the United States in Ultimatum is just as close, with shared values and ideal partnership. The feelings of anxiety and betrayal that happen after such a break, whether Trudeau and Regan or Trudeau and Trump, mimic the feelings of the 1970s.

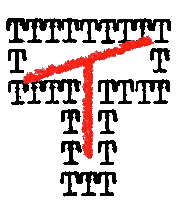

Much of Rohmer’s writing is didactic in nature. He treats his writing as a learning opportunity for the reader. Rohmer includes diagrams of airplanes, instructions for setting timed charges on oil pipelines, and methodologies for kill switches and timers. Rohmer takes the reader through his resistance fantasy (expanded upon in Exxoneration, the sequel where Canada is under United States rule), and his governance fantasy simultaneously.

Suffice to say, Rohmer is more concerned with conveying his military and aero-engineering knowledge than with deepening character relationships and motivations.

The novel concludes with the Prime Minister and Members of Parliament coming to an agreement to refuse the ultimatum. They agree with helping the United States, but resent the tactics used upon Canada as “its largest trading partner, closest ally, and primary source of natural resources and raw material. Such a course is unworthy of the fundamental precepts of freedom, justice, and liberty upon which that country was founded.” (p.214)

The President is not pleased with the selfish nature of the government, and wants to offer the “Canadian people a better opportunity to share their massive resources with us, and in exchange to participate directly in the high standard of living and superior citizenship enjoyed by the people of the United States.” (p.221). He declares Canada effectively the 51st state, dissolves the Canadian Government, and US aircraft put the nation under siege. Trump’s wet dream.

Canada has a national imagination, its own soul, however complex and varied. It is that complexity that makes it difficult for any “Annex Canada” rhetoric to get far. Yet Canadian party leaders in the year 2025 are splintered. Pollivere continues to hurl shots at Carney’s government, the system refuses to include First Nations leaders in national discussion, and no Canadian seems to know what the crisis is.

Prime Minister Carney published a book on the subject of values and nation building, but Canada remains a nation in disunity. If there is one thing true to Rohmer’s time, Canada is haunted by countless internal contradictions. When the political crisis of the second Trump presidency unravelled, many Canadian outlets recommended Ultimatum as a view into this “Canada Crisis”. Clearly, not many people did their homework, because we never had Richard Rohmer as Prime Minister and President. Canadians are a politically disengaged and misinformed people, and frankly, posting this book in an attempt to gain clicks is dishonest.

I don’t recommend reading this book to understand the geopolitical situation between the United States and Canada. Ultimatum may provide an insight into Canadian anxiety, but never truly provides solutions to sovereignty, Arctic pipelines, and the strain of elite governance. A foolish roadmap for the choppy waters ahead.

But what is far more valuable in Ultimatum is a view into the mind of Richard Rohmer, venerable war hero, national treasure, Arctic pipeline enthusiast. He currently resides in Toronto, age 101.