By Simon McNeil

What value is there in a universal technology that is destroying the world?

This is the central problem of The Tangled Lands. This book is a 2018 mosaic novel consisting of four novelettes, two by Paolo Bacigalupi and two by Tobias S. Buckell. These novelettes all share the setting of the city of Khaim and its surroundings in a world where acts of magic produce an ever-present Bramble - a fast-spreading weed whose hair-like thorns produce an unending torpor from which few ever awake. Bramble is hard to dispose of and is nourished by magic, leading to Bramble’s unstoppable expansion across the world. The wide-spread use of magic within the empire Khaim belonged to led to the complete collapse of the empire. What remains is fractured city-states connected perilously by a system of roads increasingly threatened by encroaching Bramble.

This is a challenging book to read. It’s uneven. Buckell and Bacigalupi have significant differences in style and voice which makes the transitions from one author to the other jarring and which disrupt the flow of reading. But it is also a worthy read for how it problematizes the usual concerns of climate fiction and for how said concerns might be addressed in the context of our current technological moment.

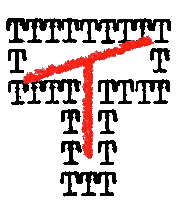

Bramble, the side-effect of magic that chokes the land and that brings total stupefaction to anyone who touches it, is an apt metaphor for what the tech industry calls “artificial intelligence” – generative technologies enabled by mass theft like ChatGPT and MidJourney. Like AI, Bramble chokes out what is useful under a thicket of useless trash. Like AI, it has alarming psychological impacts upon those who come into contact with it. People who have momentary contact with bramble become sluggish and dull. Extended or significant contact leaves people in a state of suspended animation which inevitably ends with their semi-living consumption by flies, rats and other vermin.

Magic is alienating. Being a taboo enforced with execution, you cannot talk about it with others. People who know magic hide their knowledge lest they be killed and Magister Scacz, magic’s gatekeeper, demonstrates that the best number of powerful wizards to exist in any given community is precisely one - and that one must diligently and violently ward against any interference. At its worst magic, via bramble, alienates a person from the world, leaving them in a non-communicative slumber from which they never emerge.

But, for all of this I think, the principal lesson about AI communicated by this metaphor is how little distance the world has really travelled in the last few decades. Companies like Amazon, Microsoft and Nvidia have been responsible for the construction of massive data centers. These complexes provide massive quantities of computer capacity but are incredibly expensive. With the capitalist imperative to eternal growth, Nvidia must always find a market for its GPUs and Microsoft and Amazon for their server farms. These markets must always grow. Simply put: for the companies that undergird the infrastructure of the contemporary internet to remain powerful the internet must constantly be growing.

The rest has been a search for a use-case to support this growth--be it auto-generated media, a replacement for executive assistants, or simply ducking out of writing your own emails. Before AI (and the metaverse, and NFTs,) it was blockchain. Blockchain is highly inefficient, bringing with it a total absence of optimization that leads to the consumption of significant compute and an output of heat and pollution that far outstrips its utility. As companies discovered there was no public use-case for blockchain they pivoted to gen-AI in hopes of justifying the expenditure and realizing profit on all this cancerous growth. Like blockchain, gen-AI is perversely inefficient and requires absurd levels of computer capacity. This means, like blockchain, gen-AI is terrible for the environment and contributes significantly to climate change both through the extraction of minerals for the chips, the electricity required to run the data centers and the heat they output as waste.

One might interrogate why these companies seem so beholden to such environmentally destructive and inefficient technologies. The inefficiency is the point. And this brings us to the central way in which The Tangled Lands problematizes climate fiction: the very first novelette presents us with a solution to the problem of Bramble. The alchemist who narrates the first novelette devises a machine that destroys Bramble at the root. With it, the Bramble is easily pushed back. As a side-effect, the smoke produced by this machine’s chemical processes reveals anyone who has recently used magic. It is deeply illegal to use magic but it is a law mostly understood through its uneven enforcement. Many people use a little bit of magic. You can get executed for any such use but it would depend on somebody knowing, and being able to prove, you were doing this forbidden thing. Most are clever enough to do little bits of magic here and there out of the public eye, assuring the bramble crisis worsens even as Khaim’s authorities crack down.

All this changes when the alchemist demonstrates his machine to the mayor of Khaim and to Magister Scacz – the worst offender of all when it comes to using the poisonous technology of magic. The Mayor and the magister see, in the side-effect of the machine, the opportunity to secure their power and enact a violent purge, slaughtering countless people and upending the political order of the city, then using their monopoly on the ability to clear Bramble to raise up a class of subservient stooges. The Alchemist is made a prisoner with his family held as well-kept hostages so that he can devise new machines. As the story progresses, the threats to his family escalate and the likelihood that he will be disposed of as soon as Scacz and the Mayor decide he has outlived his usefulness increases. Through cunning and boldness he manages to communicate with his family and forms a desperate plan to escape. Shockingly this plan succeeds. Barely. Though the alchemist escapes from the city to an unknown fate at the conclusion of the novelette, only Khaim has the machines that can destroy Bramble. And rather than using them to do this, the rulers use them to enforce an iron-fisted rule that allows them and their cronies to enjoy what anyone else is put to death for touching.

We must live with this knowledge throughout all the stories that follow. It is as if the authors want to say that, while the devastation of our world under the contemporary technological regime is extreme, we have all the tools at our disposal to fix it. As such, while The Tangled Lands serves as a work of climate fiction, it is much more concerned with the power systems that create, and are created by, the climate crisis and the technologies that underlie the climate crisis than it is by the phenomenon itself. Much like blockchain and gen-AI, the specifics of the phenomenon don’t really matter so much as what impact these phenomena, and the world they engender, has on people.

What should we make of the Executioneress’s tale? This second novelette does nearly as much to establish the status-quo of the Tangled Lands as the first, concentrating on the daughter of a dying executioner in Khaim who, after being forced into assuming her father’s mantle, loses her family in a bandit raid. She sets off on a journey across the wilderness that sees her become a rebel leader against an invading theocracy and then the ruler of its greatest city.

The story does play with tropes concerning gendered violence in time of war and how women are underestimated as a fighting force in ways quite similar to Shelley Parker-Chan’s She Who Became the Sun in a way that seems overt enough to bear some examination. The world of Khaim isn’t as sexist as some other fantasy worlds that interrogate gendered violence. The realities of class and of the refugee experience mostly overwhelm questions of gendered power in the book but, in this section, it’s clear that many people see fighting as principally “men’s work” and the story deploys the extent to which people underestimate a force of women (and the affective potential of grief) as a plot device that allows our story to end with the Executioneress waiting by the sea in hope that her sons arrive. But, at the same time, it proposes something a little dark: maybe we just can’t decouple from destructive technologies unless we’re forced.

The Paikans come from an island archipelago some distance away which abandoned magic or never used it. And yet, despite their total abstention, Bramble grows on their islands, fuelled by the excesses of the Empire. The Paikans insist that the people of Khaim and the other cities of the Empire are incapable of full abstention from magic. And so they kill the adults and abduct the children, indoctrinating them into a Paikan way of life. The pain of these separations is obvious; the executioneress becomes a warrior and a general and eventually a ruler simply to have the chance to see her children again. But what should we make of Paikan pessimism? They are never disproven in the narrative, after all.

Magic is wielded at length in the two later stories. In The Blacksmith’s Daughter, the central conflict involves a family of smiths crafting a set of armor for the son of a noble that has been devised to fool the magic-detection systems of Khaim. The same noble entreats Scacz, now building a castle floating in the sky as the city’s sole magic user, to punish the smiths for failing to construct the armor, accusing them of theft, though the narrative is clear he never intended to pay them for their work, and Scacz responds by casting spells designed to cause bramble to grow. In The Children of Khaim, much of the action centers around the impact of a seeking spell with deadly consequences. It seems like even in Khaim, a city that can detect magic users and that takes great satisfaction from their execution, nobody can stop using magic. This seems almost a sop to those people who call environmentally destructive technologies like generative AI inevitable: see, they know what it will do. They know the horrible consequences. And yet. And still.

I’ll be honest, I don’t know how I feel about this defeatist approach. The Paikan idea of forced generational renunciation, combined with the purging of those who will not abandon the technology is exterminism, a philosophy that dictates the best response to scarcity is the elimination of competitors for scarce resources: the same philosophy that has driven the mass oppression of immigrant workers and refugees in the United States and the UK. Four Futures, a work of speculative future history written by sociologist and Jacobin editor Peter Frase proposes exterminism as one of four possible global political responses to the collapse of Capitalism along with communism, rentism and socialism. This serves largely as a platform to advocate for Frase’s particular definition of communism as an ideal to strive toward. The seeds of that better future still exist in the escape of the Alchemist, in the existence of machines that could destroy Bramble and allow for a safe and responsible use of magic.

The third story of the book, The Children of Khaim details the struggles of a boy to find his sister, brought low by bramble stings, as he discovers the terror of the wanton flesh trade that treats bramble-sleep affected people as things that “men with soft eyes” can use. The story is possibly the darkest in a set of dark stories. After failing to find his sister at a seedy brothel, the boy casts a spell that lets him find his sister only for this spell to go awry and lead to a death, and the attention of the constabulary. But something remarkable happens. Workers who toiled alongside the boy and the girl and who seemed somewhat hostile at first glance stand up together to protect him and his sleeping sister. Their solidarity gives him the opportunity to see his sister protected against the (very slim) chance that she might reawaken. Hope comes in the form of solidarity. There is an echo of this idea in The Executioneress and her army of grieving mothers.

The challenge is that the technology is not, on its own, anywhere near sufficient. It’s not enough to say, “well we could do this if only we had the will” because will was never the problem. The issue is, rather, that those in power have a strong motivation to use technology in ways that will allow them to remain in power. The greatest threat to a communist future is that those people in charge of the bombs and the banks and the judges will say they would rather be warlords than comrades. We can make like the Executioneress and fight to end exterminism long enough to wait for the next generation to come along and hopefully be better but this seems poorly advised. The Tangled Lands proposes a somewhat defeatist view that the best we can hope for is to persist in the ruins full of the hope that some day things will be different. Hope is the principal affective vector that our protagonists move toward.

They all end their stories not realizing some great victory but rather hoping that they might achieve it. Just not now. But I think it’s important to look at solidarity as the vector through which hope is achieved. We see it in the way the Alchemist’s family secures his escape, we see it in the army of grieving mothers. We see it in a community of laborers who stand together to protect the dignity of a child who might very well be dead and we see it, less perfectly, in the story of a blacksmith’s daughter who shows how quickly people fold when they don’t have solidarity. In every case, a person is not an island. Whether it’s family, community or even a vanguard of those who have suffered as we have suffered, we can only achieve a hope for a better future together. Whether we form this solidarity to simply persist or to rebel against exterminist excess, we must always remember that we are not alone.

Simon McNeil is a genre author and critic living on a small permacultural farm in Prince Edward Island, Canada with his wife, daughter and various animal companions. He enjoys martial arts movies, tabletop games and weird books.

Editorial Disclosure: Typebar Magazine's editor attended the MFA program where Tobias Buckell is a professor.