By Matthew Claxton

Written science fiction is dying. Long term trends see fewer books making their way to shelves in the sci-fi section. Although sci-fi looks healthy from a perspective of films, video games, and TV, written sci-fi has long been the wellspring of the vast majority of new ideas, aesthetics, movements, and tropes within the genre. If you saw it on a screen, it was almost certainly found on a printed page first.

Yet even as the clanking genre-machinery of specialty publishers and imprints seems to be grinding to a halt, written sci-fi is reaching new, potentially larger audiences than ever before.

Both can be true at once, because sci-fi has gone mainstream. Stories featuring time travel, cloning, AI, and apocalyptic plagues find themselves between respectable covers and sold to literary purists, book club members, and others who would never in a million years consider themselves sci-fi fans.

This new iteration of written science fiction isn’t quite the same as the old one, in ways both positive and, potentially, negative.

Simon McNeil chronicled the slow death of the field in Typebar Magazine Issue 1. Long twinned with and considered by many readers interchangeable with fantasy, stories that engage with technologies and imagined futures are rarer, while fantasy goes from strength to strength, spinning off new subgenres like romantasy and finding new readers. (Goodreads had Fantasy, Romantasy, and YA Fantasy as separate categories in its annual awards poll last year – science fiction had one category.) The books that are categorized as strictly science fiction are increasingly dominated by classics and media franchise tie-ins – if your bookstore has any sci-fi novels, it definitely has a movie-cover edition of Dune.

But you could wander out of the science fiction section, and pick up a copy of Sea of Tranquility by Emily St. John Mandel, Samantha Harvey’s Orbital, Martin MacInnes’s In Ascension, or Ian McEwan’s newest, What Can We Know. Every one of them has space travel or takes place in an extrapolated future, yet they’re more likely to have been nominated for the Booker Prize than a Hugo Award.

To understand what’s happening now, we’re going to need a brief detour back to the birth of science fiction as a commercial genre.

Genres begin with stories and novels that seem at first sui generis, but as more examples appear, readers and critics spot the common features. Fans accrete around them, new writers produce works that use the same plot structures, techniques, and literary tropes.

All of this happened to science fiction between around 1817 – when Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, a gothic novel about literature’s first mad scientist, was published – and the mid-1920s. In between were well-remembered writers Jules Verne with his submarines and airships and extraordinary voyages, and H.G. Wells with his Martian invaders, uplifted animals, and time machine.

There were also countless forgotten works of proto-science fiction.

There were hundreds of “edisonades” about super-intelligent inventor-heroes in American dime novels, starting with The Steam Man of the Prairies in 1868.

Utopian fiction included tales of perfected or satirical futures in Samuel Butler’s Erewhon, William Morris’s News From Nowhere, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s Vril.

In 1912, the same year his character Tarzan debuted, Edgar Rice Burroughs also created John Carter, in A Princess of Mars, a swashbuckling tale of sword-and-pistol battles with alien tharks and therns, along with nude, egg-laying Martian princesses.

And there were pure oddities like David Lindsay’s 1920 novel A Voyage to Arcturus, in which the hero immediately grows several new organs on arrival, including a tentacle emerging from his heart.

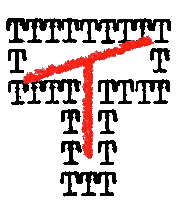

All of these are, from our later perspective, recognizably science fiction. But they were scattered. There were no science fiction sections in the bookstores or libraries, there were no publishing house editors clamouring for more of it. The term science fiction had not been invented! Proto-sci-fi in the 1910s and ‘20s was published for the most part in adventure pulps, alongside westerns, pirate tales, sports stories, mysteries, and “weird tales” that were the forerunners of modern sword and sorcery and cosmic horror.

Slowly, periodical publishers realized that there were audiences who would buy the same kinds of stories over and over and over. Mysteries and detective novels broke from the pack first in the 1910s, and then in the mid-1920s pulp publishers started putting out dozens of single-genre titles (although no one was yet using the word genre). According to Andrew Goldstone’s 2023 essay “Origins of the U.S. Genre System,” in 1924 a survey of the field found just four: Sea Stories, Sport Story, Western Story, and Detective Story. The other magazines published a grab-bag of types. By the end of the decade, though, there were 123 pulps that could be identified by a single genre.

The publisher who successfully broke sci-fi out from the pack was Hugo Gernsback. The former electronics importer started Amazing Stories, the first all-sci-fi magazine in 1926 (he called it “scientifiction” for a while; “science fiction” emerged as a term of art over the next couple of years), and would go on to found several more magazines. Much of his early output re-printed the works of authors like Wells and Burroughs, but soon he needed new stories. The regularity of monthly magazines worked its magic on kids like future editor and writer Frederick Pohl.

“When another science fiction magazine came my way, a few months later, it was like Christmas…” he wrote in his memoir, The Way the Future Was. “Given two examples, I was at last able to deduce the probability of more, and the general concept of ‘science fiction magazines’ became part of my life.”

It became part of the lives of a host of other mostly-young readers, creating the first generation of people who conceptualized themselves as science fiction fans, and who aspired to be science fiction writers, editors, or publishers.

This was the tipping point, where a genre – stories sharing themes and plot elements – became a commercial genre. Now there were editors and writers and fans locked together in a feedback loop. The letters columns of the pulps and the early fanzines became a space where the nature of science fiction could be contested, defined, contained. Through the first fan organizations – one of them also organized by Gernsback (Pohl: “What Hugo hoped for from the Science Fiction League was a plain buck-hustle, a way of keeping readers loyal.”) and the first conventions, they began gathering in person. The genre machinery clunked and clanked into motion.

From the outside, carving off “serious literature” from the newly emerged genres – and this applied as much to romance and mystery and cowboy tales as sci-fi – created a more elevated realm. High-minded writers, whether cursed with poor sales or even worse, with popular success, could console themselves that at least they weren’t writing genre fiction.

Let’s jump forward about sixty years now, to the 1980s.

By now, a connoisseur can not only spot an SF novel cover from ten feet away, they can likely discern its place in one of the many sub-genres or movements that have arisen – military SF, New Wave, hard SF, feminist science fiction, space opera, and so on.

In 1986, author Michael Swanwick’s essay A User’s Guide to the Postmoderns took a look at two then-vital movements among younger writers – the cyberpunks, and the (now largely forgotten) humanists.

“It’s been said that every generation creates its own horde of invading barbarians in its young,” Swanwick began. “This is certainly the case in the radioactive hothouse of scene fiction, where new literary generations arise once every five or so years to challenge the establishment with a new vision of how the stuff ought to be written.”

Swanwick paints a picture of constant internal roil, of a genre that has never stopped debating what it is, where it’s going, what it should be about. If that was once true, that energy has ebbed, with would-be revolutions and new genres (cli-fi, Mundane SF) failing to find a foothold.

Instead, in the last decade the science fiction and fantasy community has spent a lot of energy defending both genres from people determined to drag them back in time instead of finding a way forward. There’ve always been those grumbling about the “good old days,” but it coalesced from 2013 to 2017 into the Sad Puppies/Rabid Puppies movements.*

Just as science fiction was finally seeing serious inroads by a new generation of BIPOC and queer authors, as well as giving belated acknowledgement to their predecessors like Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany, a gaggle of right-wing writers – some full-on white nationalists – tried to stack the fan-voted Hugo categories for themselves and their friends. While their political animus was obvious, they claimed they were simply defending good ol’ fashioned sci-fi from anything they perceived as either too literary, or “political.”

“The fact that I write unabashed pulp action that isn’t heavy-handed message fic annoys the literati to no end,” wrote fantasy author Larry Correia in the post that kicked off the Sad Puppies movement.

Although the Sad/Rabid Puppies used their rejection of any form of elevated writing as a club to beat their political enemies, they really do despise it – despite the fact that most of them were children or not yet born when the New Wave movement started in the 1960s, ushering in literary and postmodern techniques to sci-fi, upending the dominance of pulp-style writing.

Science fiction had to fight itself, not for new ideas, but simply for the right to write above a sixth-grade level.

While this attempted counter-revolution was consuming attention inside the genre, science fiction as a mode of literature was slipping increasingly out of the control of the genre machine.

In truth, there’s always been science fiction produced outside of the machine. Writers who are covered in the New York Times and Paris Review instead of Locus Magazine have been sneaking into the sci-fi clubhouse, making off with the furniture and tchotchkes, and putting them to their own use for generations.

Britain was a perennial source of incursions, since the barriers between sci-fi and respectable (or at least popular) literature were lower there. Writers like J.G. Ballard and John Wyndham helped pave the way for writers who would jump back and forth, genre to mainstream, like Iain M. Banks and Kazuo Ishiguro. Britain also contributed George Orwell’s 1984 and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, novels respectable enough that they could be taught in schools, despite their science fictional trappings.

Writers in translation also had more leeway. You didn’t have to be ashamed of reading Stanislaw Lem or Haruki Murakami, despite the rocketships and unicorns.

In North America, writers had to be a bit more circumspect, but if you called your writing satire, you could throw in all sorts of oddities. So we got Kurt Vonnegut’s novels with their alien invasions, superweapons, and time travel. Vladimir Nabokov’s Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle is set in an alternate world where North America is largely settled by Russian and French speakers. William Burroughs’ works were odd enough that they’d inspire a coming generation of cyberpunk writers, and Thomas Pynchon played with sci-fi tropes sufficiently well that Gravity’s Rainbow scored a Hugo nomination.

There were also a few writers from within the genre who were canonized as worth reading by wider audiences. Philip K. Dick received this treatment posthumously, while William Gibson coined the word “cyberspace” and was acclaimed a sort of guru of the information age. More recently, Jeff VanderMeer has successfully straddled the genre and literary world, after starting out in the ferment of the New Weird movement.

The most important figure in the long march of science fiction through non-genre literature, however, may have been Margaret Atwood. The Canadian author of 1985’s The Handmaid’s Tale was raised on pulp sci-fi before turning her back on it once she became a serious poet and novelist. But despite her well-documented refusal to acknowledge her writing as science fiction, she kept returning to the genre. She embedded a sci-fi story in 2000’s The Blind Assassin, then dove in fully with 2003’s Oryx and Crake and its two sequels.

By the time Atwood wrote Oryx and Crake, with its genetic engineering and world-ending plot, the breakout of science fiction into the rest of the bookstore was fully underway, having colonized pop culture via TV, movies, and video games.

The early pulps and proto-genre works provided fodder for comic book writers, for Rod Serling and Gene Roddenberry, for the writers of cheap rocket-adventure serials in the 1940s and drive-in atomic monster movies. Those fertilized the minds of George Lucas and Steven Spielberg, whose 1970s and ‘80s films would emerge at the perfect moment to seed science fiction tropes into the broader culture.

When Atwood published The Handmaid’s Tale, she could trust that her readership would be familiar with the ideas of a near-future dystopia thanks to Orwell and Huxley. By 2003, a broader familiarity had been achieved – who among her readers would have avoided ever seeing Star Wars, Star Trek, 2001: A Space Odyssey, Back to the Future, or The X-Files?

A new generation of writers took advantage of this, publishing works that could not, by definition, be anything other than science fiction, but without worrying about labels.

Some came from deep within the genre. Between the 1989 publication of his first short story and 1998, Jonathan Lethem was, definitively, a sci-fi writer. His stories appeared in places like The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction; his novels involved alien planets and advanced physics; he wrote an entire story in response to a critical comment from Bruce Sterling.

Then in 1998 he wrote the essay “Close Encounters: The Squandered Promise of Science Fiction” in the Village Voice Literary Supplement, excoriating the genre for essentially turning its back on its post-New Wave chance to become serious literature, to dissolve into the wider publishing world.

“Fearing the loss of a distinctive oppositional identity, and bitter over a lack of access to the ivory tower, SF took a step backward, away from its broadest literary aspirations. Not that SF of brilliance wasn't written in the years following, but with a few key exceptions it was overwhelmed on the shelves (and award ballots) by a reactionary SF as artistically dire as it was comfortingly familiar,” Lethem wrote.

The next year, he broke out into the mainstream with Motherless Brooklyn, a novel without a scrap of science fiction in it. Having re-defined his writerly identity, his follow-ups might include the fantastic, but would not be shelved between those of his Sycamore Hill Writers Workshop colleagues Nancy Kress and Maureen F. McHugh. Chronic City, for example, is a tale of people trapped in a fractured, imperfectly simulated reality, but good luck learning that from the dust jacket.

Michael Chabon made the pilgrimage in the opposite direction, writing two contemporary novels, including the acclaimed Wonder Boys, winning the 2001 Pulitzer for the geek-adjacent The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, and advocating forcefully for the return of plot – and genre elements – to short fiction by editing McSweeney’s Mammoth Treasury of Thrilling Tales in 2002, before diving into alt-history with The Yiddish Policeman’s Union.

In 2003, the same year Oryx & Crake was published, Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife became a publishing sensation. A novel that situates its premise firmly in science fictional territory – protagonist Henry DeTamble’s jumps in time are the result of a hereditary genetic condition – it sold millions of copies.

Maybe it was the one-two punch of Oryx and Crake and Time Traveller’s Wife in the same year that knocked down some invisible publishing barrier. In retrospect, it seems like the year things really changed.

One of the best surveys of this trend is the list of nominees for the annual Arthur C. Clarke Award, a juried prize for the best science fiction novel. Although it’s always had works published outside genre – the very first winner was Handmaid’s Tale – it’s after 2004 that the list starts to become a heady mix. The Time Traveller’s Wife and David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas competed with China Mieville’s Iron Council and Neal Stephenson’s The System of the World in 2005. Authors like Sarah Hall, Richard Powers, and Kazuo Ishiguro make appearances alongside genre stalwarts. 2022 winner Deep Wheel Orcadia is a novel-length poem by Harry Josephine Giles, written in Orcadian Scots, set on a space station.

In recent years, the winners have increasingly been writers who are outsiders to the genre, who write on both sides of the divide, or who simply don’t acknowledge that a divide exists at all. Almost none of them are published by sci-fi imprints.

Meanwhile, awards originally created to acknowledge science fiction – especially the Hugo and Nebula Awards – are now dominated by fantasy works, in line with the dwindling importance of science fiction to the broader field of fantastic literature. Many fans and writers declare there is simply no difference between sci-fi and fantasy. (This is why, when asked for a recommendation for a good fantasy novel, I tell people to read The Peripheral, The Dispossessed, or Embassytown.**)

If the genre-machine finally came to a halt today, would it even matter? It might be a little harder for genre obsessives to find what we want, scattered in the general fiction section of the bookstores, but it’s out there, right?

But this new stream of sci-fi isn’t quite the same as the product of the genre machinery.

On the positive side, for those who do care about things like prose, theme, and character development, post-sci-fi tends to aim higher than the average genre-identified sci-fi novel. When your peers are folks like Ishiguro and Ian McEwan and Philip Roth, you have to step up your game. (Which is not to say that genre-machine SF is without literary merit, but we’ve just gone over the fact that there is a vocal faction who actively despises it, and plenty of readers who don’t care much.)

A huge amount (not all, but a lot) of genre sci-fi still relies on pulpy adventure plots, on absurdly high stakes, on action scenes that end with identifiable villains getting their just desserts. Post-sci-fi, written for an audience that moved on from those plots in grade school, isn’t beholden to those structures. It is as likely to feature refugees as heroic rebels, senior citizens as youngsters coming of age, and to focus on the struggles of a family as a race to defuse a bomb.

They’re also free to allow the science fictional elements of their stories develop slowly, to emerge only in the latter half of the text, or to remain an isolated thread in a larger tapestry, all of which are anathema to genre-machine publishing, which generally wants its spaceships front-and-centre early on, to reassure readers they’re getting what they paid for.

Novels like Laure Jean McKay’s The Animals In That Country, about an alcoholic woman trying to find her granddaughter as Australian society crumbles amid a plague that allows animal-human communication, is one of the best science fiction novels I’ve read in years. It was published by Scribe, a small, independent Australian house. Would Animals In That Country have found a home at Tor, or Del Rey?

Maybe, and maybe not. Some of this past year’s Clarke Award nominees could have successfully made the jump in either direction. Ian Green’s Extremophile is a biopunk adventure tale with its feet planted squarely in the middle of the genre (in spite of eschewing quotation marks) yet it was published by small press Head of Zeus.

But the most prominent novel in the most recent nominee’s list is the one that got me thinking about sci-fi and post-sci-fi, about whether you need a genre machine to produce genre novels. It’s Kaliane Bradley’s The Ministry of Time.

Published by Sceptre (the same house that published Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas), Ministry of Time is about a British civil servant assigned to live with, monitor, and acclimate one of six people plucked from the past in a secret experimental project. It’s a romance and a thriller, a book that is at its most charming when its somewhat spiky protagonist is bouncing off her charge, who finds himself the lone survivor of the Franklin Expedition and displaced by more than a century and a half from everyone and everything he knows.

It’s a good novel, an interesting novel, but also a novel that contains no surprises for a typical science fiction reader. This is Time Travel 101, with only a couple of twists, which will be seen coming fifty pages away by genre fanatics.

And this is also typical of post-sci-fi novels. Writing for a general audience, there can be few innovations in the ideas that underpin science fiction itself.

Post-sci-fi novels utilize alternate history, time travel, pandemics, near-future AI, a bit of cloning and perhaps a dash of Matrix-style cyberpunk. The settings tend towards the contemporary or the very near future. Only a handful venture into areas that have been core to genre-machine sci-fi, like space opera, or post-human and post-singularity tales. The central idea is often presented as something new in the world – these stories are seldom have settings where time travel or cloning or space colonization has been long established, has wrought social changes over generations. Nor do they tend to stack ideas – it’s cloning or AI, but rarely both.

I would love to sit down with an editor at Sceptre, and ask if they could have successfully sold space operas like Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice, Arkady Martine’s A Memory Called Empire, or Ken MacLeod’s Cosmonaut Keep, to a general audience. Yes, no? I genuinely don’t know what the answer would be.

Iain M. Banks was successful in both mainstream and science fiction writing, but if he’d sent The Player of Games to the editor of his contemporary books, what would the reception have been? Banks’s novels set in The Culture – a post-scarcity anarchist space empire guarded by superintelligent AI starships with names like “Just Read The Instructions” and “Of Course I Still Love You” – feels like a hard sell to fans of Ishiguro and McEwan, at least to me.

Then there are novels that push the boundaries of science fiction and fantasy, or mash them up with wild abandon. Vajra Chandrasekera’s Rakesfall is an amazing melange of fantasy, horror, and far-future post-human science fiction. One of the most literary novels I’ve read in recent years, it’s hard to imagine it being offered to a general readership. If The Ministry of Time allows readers to explore a new neighbourhood adjacent to their own, Rakesfall is well off the map.

Novels like Rakesfall and Ancillary Justice and Player of Games exist because that recursive fandom-author-publisher loop keeps bringing in new people, and teaching them the grammar of science fiction, and then making them into new authors.

Having a genre with boundaries can lead to exclusionary gatekeeping. But it also creates a place for play and experimentation like no other. Authors have spent almost a century now creating new toys, sharing them, modifying them, sometimes breaking them just to see what would happen.

If genre-machine sci-fi dies, we’ll still have great post-science fiction novels for years to come. But the diffusion of ideas from one author to many, what Swanwick termed the “radioactive hothouse” – that could die. If it does, written science fiction could become a tree with its roots cut off.

Without genre sci-fi as a safe place to iterate, to build new ideas, to try out concepts that push things just a little bit farther, without an audience that can be relied on to understand shorthand like relativistic space flight and cortical implants and transgenic organ transplants, could science fiction stagnate? It might stop being unselfconscious enough to be weird and nerdy for the sake of being weird and nerdy, a process which produces a lot of junk, and also sometimes wonders.

If that realm dies, there’s a real possibility that post-sci-fi dies next. Deprived of new ideas that can slowly work their way out via pop culture osmosis, it’ll grow stale. And its authors, who can work with equal facility in fantastic or mimetic modes, will pack up their spaceships and time machines, and store them in their mental attics to gather dust.

Maybe I’m wrong, maybe a science fiction genre diffused among many writers and editors at conventional publishers can sustain itself. Maybe the hothouse is no longer necessary.

It’s also possible that we’re declaring genre sci-fi dead before it’s quite kicked the bucket. Horror literature has (appropriately) died and returned from its own grave, stronger than ever.

But genres do have lifespans; most are born, they live, and they die. Whether it’s jazz and rock, or westerns and sea stories, some fade away, and most are lucky to make it to a century. (Except romance and mystery. Love and murder will outlive us all.)

If science fiction dies, I can’t pretend it will be a staggering existential loss for humanity. Was the loss of the sea story as a distinct genre a tragedy? Do we need another hundred years of stories about cowboys with six shooters? We pretend that science fiction is useful, that it serves as a warning system. But as Simon McNeil noted in his essay, “We got to one of the futures Science Fiction proposed, and it sucked.” Dire predictions of corporate hegemony and imminent authoritarian rule had precisely zero impact on the real world. Elon Musk named his rocket booster recovery barges after Banks’ benevolent anarcho-communist starships, showing all the self-awareness of a small damp rock.

It’s pure selfish love that animates my desire to see more science fiction in the world. But isn’t that something all of us feel towards the art that lights us up?

Science fiction is dying. Post-sci-fi is growing stronger. I hope it can flourish, and that the old genre machine can cough up a few more great books before exploding in a radioactive mushroom cloud.

*The campaigns were named after a joke about the Sarah McLachlan commercials for the SPCA. It doesn’t make any more sense in context.

**For decades, science fiction was the dominant of the paired genres, and many of its fans looked down on fantasy; some fantasy fans are determined to get in their kicks now that the shoe is on the other foot. Some fans are actively rooting for the death of the science fiction genre.

Matthew Claxton's short fiction has appeared in Asimov's Science Fiction, Escape Pod, and SciFiction over the years. His story Terminal City Dogs, about graffiti, public acts of mourning, and a world-weary detective, will be out in Analog Science Fiction & Fact's July/August issue. When he's not writing made-up stories, he's a local newspaper reporter in the suburbs of Vancouver, British Columbia. He knows more than is necessary about cyberpunk, local land use regulations, and dinosaurs.